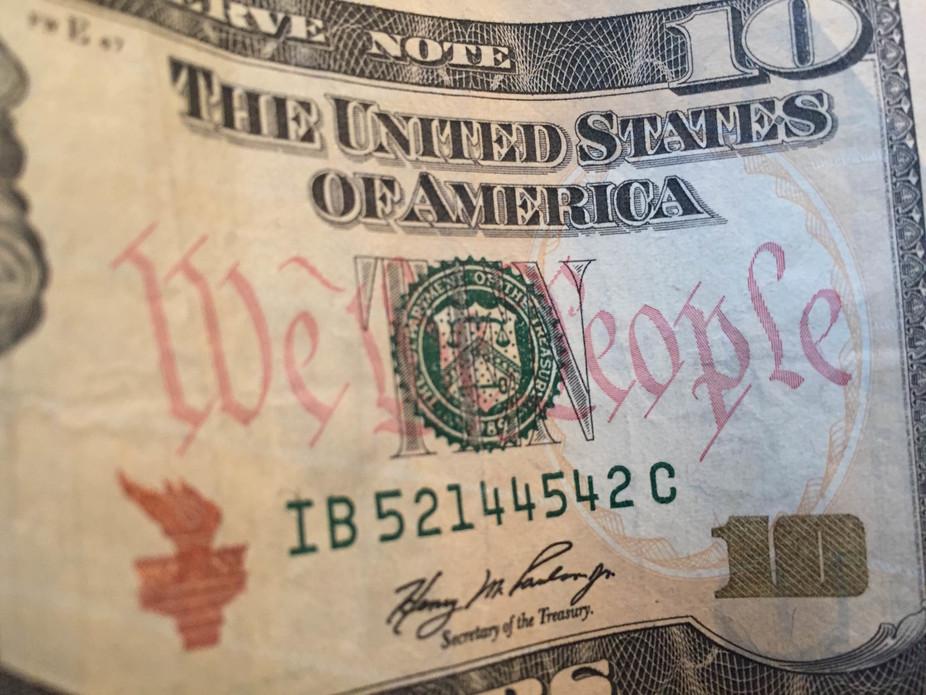

A persistent question raised in this presidential election cycle is whether assumptions about American politics need to be rewritten, especially those related to money.

The rise of self-funded Donald Trump and small-donor-supported Sen. Bernie Sanders has led some to argue that we should worry much less about the harmful effects of money on politics.

In my forthcoming book, “Pay-to-Play Politics: How Money Defines the American Democracy,“ I show why the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision was expected to stop candidates who didn’t have the financial aid of super PACs or mega-contributors. Yet, so far during this campaign cycle, super PACs have done little to back the successful campaigns of Trump or Sanders. In fact, PACs have recently done more to oppose these candidates.

So should we put to rest our concerns that unchecked money will determine electoral outcomes?