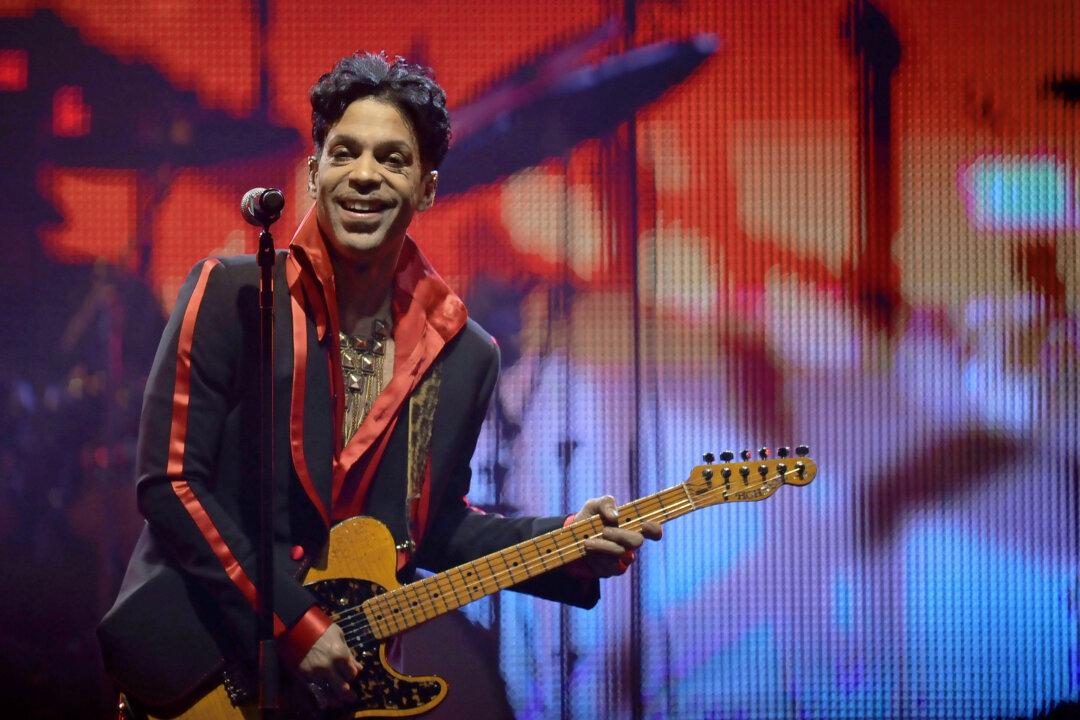

Prince’s autopsy has determined that the artist died of an accidental overdose of the synthetic opioid fentanyl. The news comes on the heels of the death of former Megadeth drummer Nick Menza, who collapsed on stage and died in late May.

Indeed, it seems as though before we can even finish mourning the loss of one pop star, another falls. There’s no shortage of groundbreaking artists who die prematurely, whether it’s Michael Jackson, Elvis Presley, or Hank Williams.

As a physician, I’ve begun to wonder: Is being a superstar incompatible with a long, healthy life? Are there certain conditions that are more likely to cause a star’s demise? And finally, what might be some of the underlying reasons for these early deaths?

To find out the answer to each of these questions, I analyzed the 252 individuals who made Rolling Stone’s list of the 100 greatest artists of the rock & roll era.

More Than Their Share of Accidents

To date, 82 of the 252 members of this elite group have died.

There were six homicides, which occurred for a range of reasons, from the psychiatric obsession that led to the shooting of John Lennon to the planned “hits” on rappers Tupac Shakur and Jam Master Jay. There’s still a good deal of controversy about the shooting of Sam Cooke by a female hotel manager (who was likely protecting a prostitute who had robbed Cooke). Al Jackson Jr., the renowned drummer with Booker T & the MGs, was shot in the back five times in 1975 by a burglar in a case that still baffles authorities.

An accident can happen to anyone, but these artists seem to have more than their share. There were numerous accidental overdoses—Sid Vicious of the Sex Pistols at age 21, David Ruffin of the Temptations at 50, The Drifters’ Rudy Lewis at 27, and country great Gram Parsons, who was found dead at 26.

And while your odds of dying in a plane crash are about one in five million, if you’re on Rolling Stone’s list, those odds jump to one in 84: Buddy Holly, Otis Redding, and Ronnie Van Zant of the Lynyrd Skynyrd Band all died in airplane accidents while on tour.

A Drink, a Smoke, and a Jolt

Among the general population, liver-related diseases are behind only 1.4 percent of deaths. Among the Rolling Stone’s 100 Greatest Artists, however, the rate is three times that.

It’s likely tied to the elevated alcohol and drug use among artists. Liver bile duct cancers—which are extremely rare—happened to two of the top 100, with Ray Manzarek of The Doors and Tommy Ramone of the Ramones both succumbing prematurely from a cancer that normally affects one in 100,000 people a year.

The vast majority of those on Rolling Stone’s list were born in the 1940s and reached maturity during the 1960s, when tobacco smoking peaked. So not surprisingly, a significant portion of artists died from lung cancer: George Harrison of the Beatles at age 58, Carl Wilson of the Beach Boys at 51, Richard White of Pink Floyd at 65, Eddie Kendricks of the Temptations at 52, and Obie Benson of the Four Tops at 69. Throat cancer—also linked with smoking—caused the deaths of country great Carl Perkins at 65 and Levon Helm of The Band at 71.