After 24 hours in the custody of officers with the Beijing Public Security Bureau, Chinese activist Hu Jia was released to his home where he was immediately put under house arrest.

“Our next target will be you” was the ominous warning given to him by security agents, Hu said.

He believes that he is likely to be interrogated again, and if the authorities choose to prosecute him — a distinct possibility, he said — the punishment could be severe.

Since 2004 Hu Jia, and later his wife Zeng Jinyan, has been a target for official harassment and punishment, aimed at deterring him from engaging in activism against the Party’s human rights abuses.

Most recently he has been active on email, Twitter, and other forums online, contacting journalists, diplomats, and other activists, to keep them informed of the trial against Xu Zhiyong, a founder of the New Citizens Movements, which aims to make the Communist Party more accountable. He has also called for memorialization of the victims of the 1989 Tiananmen massacre, organized hunger strikes, and engaged in other forms of activism.

If he is indeed sentenced, Hu said, the punishment could far exceed the four years recently dealt out to Xu Zhiyong.

“Xu Zhiyong protected rights in a peaceful way. And he wasn’t involved in sensitive issues, such as the June 4th Movement and the Falun Gong issue. However, the authorities sentenced him four years in prison,” Hu said, “It means that the authorities want to crack down on influential people.”

Hu has engaged in activism around the June 4 massacre, and has spoken to media outlets criticizing the persecution of the Falun Gong spiritual practice, considered one of the authorities’ most sensitive political issues.

“The police were preparing ‘materials’ this time to accuse me of ‘disturbing public order’ or ‘inciting subversion of state power,’” Hu said. “If Xu Zhiyong gets a four year sentence, then let’s see how I should be sentenced.”

He added that if he were accused of “inciting subversion of state power,” he would be classed as a recidivist, which carries a minimum sentence of 11 years, he said.

Hu Jia was sentenced three and half years in prison in 2008 for “inciting subversion of state power” due to his active involvement in rights activities in China.

Six policemen had brought to his recent interrogation a dossier of materials to demonstrate the claim. These included Twitter posts he had made, pictures he’d uploaded, and news reports containing interviews he gave to overseas media agencies.

All that writing and talking put pressure on the authorities’ “maintenance of stability,” the police told him.

The “stability maintenance system has become a mafia in society now, which damages China’s rule of law and social justice,” Hu said. “As a citizen, I have the right to speak, and I fight against illegal suppression that takes my rights away.”

He continued: “I have different opinions from the authorities on Falun Gong, the June 4 Movement, Xinjiang, and Tibet issues, and I am critical of the Chinese Communist Party’s historical issues. This is my right, that no organization, group, or form of government can suppress. Keeping silent is being an accomplice. I’ll continue doing what I’m supposed to do.”

Hu, 40, has been a democracy activist, environmentalist, and advocate for AIDS victims for many years. In 2008 he was awarded the Sakharov Prize, one of the highest honors in the human rights field, by the European Parliament. He was in prison at the time.

Another Chinese Rights Activist Sees Himself on Chopping Block

The Chinese activist Hu Jia suspects that the authorities may be preparing to sentence him to jail.

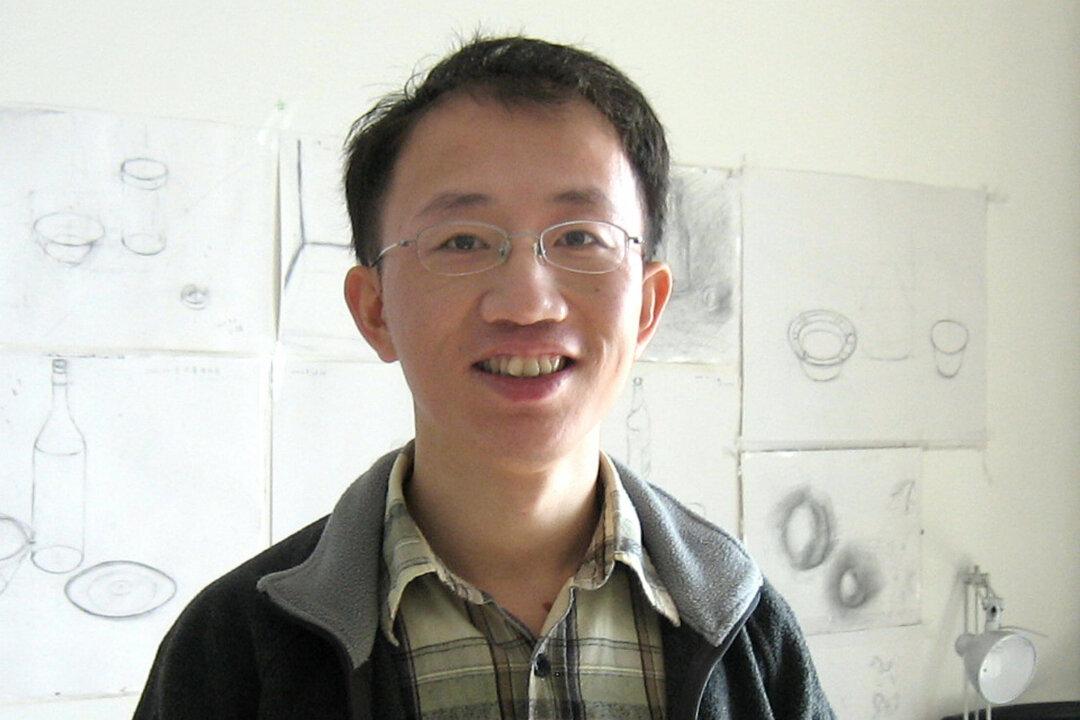

Hu Jia, a high-profile civil rights activist, welcomes a foreign journalist to his home in Beijing on Jan. 3, 2007. Hu has been threatened with a lengthy prison sentence for his activism. VERNA YU/AFP/Getty Images

|Updated: