Even in modern times, individuals about to undergo brain surgery fear the procedure—and with good reason. The cranial cavity is one of the most delicate regions of the human anatomy, and the brain a treasure to which surgeons accord the utmost respect. People instinctively know that if one were to accidentally inflict the slightest damage on a brain, the consequences could be drastic.

But what would appear to be the most daring feat of modern medicine is, surprisingly, a procedure which enjoys the most ancient history. Trepanation—the practice of carving or drilling a hole in a skull—is something man has practiced around the world for thousands of years. Trepanned skulls have been found in different parts of the planet, including in the “New World” remains of pre-Columbian cultures, beginning with a Peruvian specimen discovered in 1863.

Other examples date to the Neolithic (modern stone age), such as the 5000 year old skull with a double trepanation found in France. The degree to which the skull had healed is clear evidence that the individual lived many years after enduring this delicate operation. Moving further back in history, more evidence of these practices have been found from the Mesolithic (middle stone age), between 10,000 and 5,000 years into the past. The oldest trepanned skull discovered was found in the Ukraine in 1966, and dates from between 8,020 and 7,620 years—a time when most archeologists believe that man had only just moved from their cave dwelling days.

More Than Medicine

The finality with which these complicated procedures were performed suggest a high degree of medical skill, even though some anthropologists also attribute them to mystic rituals, given the quantity of trepanned skulls found in some places. In Baumes-Chaudes, France, of the 350 skulls inspected, a total of 60 had evidence of trepanation.

With such a curiously large proportion of trepanned skulls, some suggest that this “privilege” was afforded to a particular segment of the population. The pharaohs of Egypt for example, at some point in their lives had their skulls trepanned to, as it is claimed, make it easier for their souls to leave their bodies after death.

Today, medical doctors resort to this delicate method only to relieve pressure from a patient’s skull and drain hemorrhages, but otherwise caution against any undue damage to the brain’s bony protection. However, many suggest that ancients had reasons other than medical necessity for opening the head.

While some claim our ancestors used trepanation to cure mental illness—hoping to free the disturbed patient’s brain from the torment of possessing ghosts or spirits—other researchers say that the ancient opening of skulls was a way to offer an ecstatic spiritual experience. Such a belief has persisted even in modern times. In 1962, Dutchman Bart Hughes published “The Mechanism of Brainblood volume,” positing that by carving a hole in one’s skull, the blood-brain volume increases. In so doing, Hughes believed that the trepanned individual could raise their consciousness, with a heightened awareness closer to that of a young child with its corresponding ‘soft spot.’ By standing on one’s head, or ingesting plants or herbs that increase blood flow to the brain, a similar state can temporarily be attained. Hughes, however, was interested in a more permanent condition than mere herbs would allow and performed the procedure on himself in 1965. A few individuals have followed in Hughes’ footsteps; most notably, the artist Amanda Feilding who recorded her own foray into the bloody endeavor in the documentary, “Heartbeat in the Brain.”

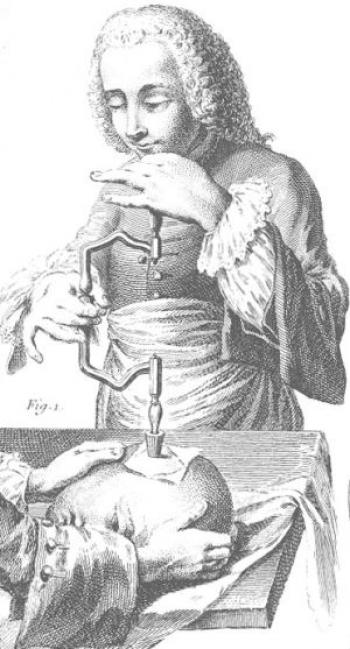

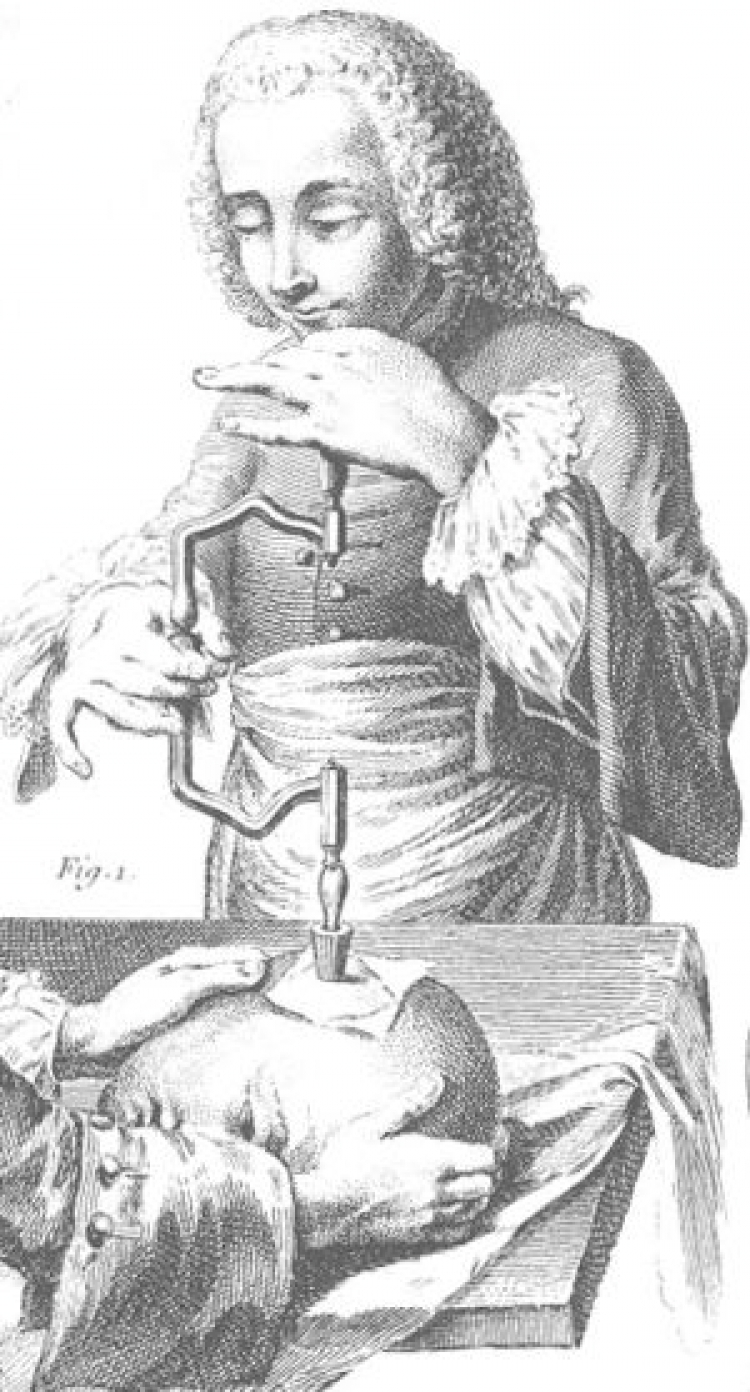

Tools of Trepanation

In some ancient medical practices, if a patient suffered headaches due to a tumor, the doctor used a tool to hit different parts of the head. When the individual howled in pain, the practitioner was certain the tumor had been found. Later the operation was performed with the patient under some primitive anesthetic. The specialist cut the scalp and then broke the bone with their rustic trepanator, taking care not to damage the brain. How they cut and extracted the fragment of bone remains a mystery, since the skull proves not an easy thing to pierce. Once the operation was finished (probably under terrible sterility conditions), the soft tissues would be sewn shut. Given that there was no modern prosthesis, the broken skull fragment could not be reinserted. Eventually, new skin would grow over the hole.

The ancient Incas possessed a special blade called a ‘tumi’ to perform the procedure. The now ubiquitous emblem— the adopted symbol of the Peruvian Academy of Surgery—is held in high esteem as an essential part of ancient Incan culture, and is used extensively to promote Peruvian tourism. The enigmatic blade features a man with an elaborate headdress, standing atop what looks like a shovel-shaped knife. This sacred object has a history that even predates the Incan civilization. In 2006, 12 tumis were found in an ancient pre-Incan Peruvian tomb complex.

Hippocrates suggested trepanning for injuries to the head and the ancient Greeks had several instruments to perform the procedure. One was the t-shaped ‘terebra’ which worked much like a primitive drill.

While ancient Egypt could boast of a wide array of relatively advanced medical devices, researchers believe that they performed some of their trepanations with a hammer and chisel. An interesting fact to note in the ancient Egyptian procedure was the intervention of a “hemostatic.” This ancient medical specialist had the power, supposedly, to stop hemorrhages solely with his presence in the operating room.

Trepanation has evolved over 10,000 years leading to standard modern medical procedure, yet the medical community largely sternly warns against unnecessarily pursuing trepanation due to the several lethal consequences that could develop. Despite the claims of euphoria that contemporary trepanation advocates insist result from penetrating the skull, many medical professionals counter that the supposed benefits are unlikely to occur and not worth the risk. So how did trepanation originate and who were the first surgeons? Did so many ancient people simply seek to relieve severe headaches, or does the significant array of specimens found worldwide suggest that our ancestors had other motives to prompt undergoing such a risky operation?