In the 8th century B.C., the Greek poet Hesiod described in his “Theogony” a place at the end of the Earth where the gorgons dwell, where the god Atlas appears as a giant mountain, and where a great chasm contains treacherous seas.

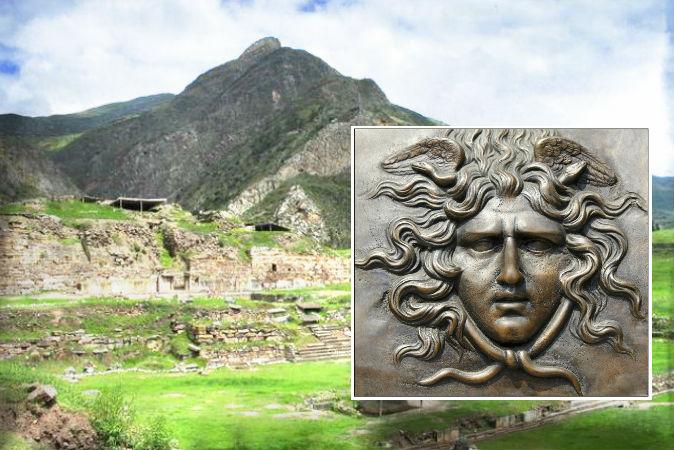

Hesiod’s description seems to match the mysterious labyrinth ruins of Chavin de Huantar in the Peruvian Andes, according to Dr. Enrico Mattievich, a retired professor of physics from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) in Brazil. Dr. Mattievich wrote a book titled “Journey to the Mythological Inferno,” in 2011 which suggests the Greek epic hero Odysseus’s journey to the underworld is set in South America.

Part of this book explores the similarities between Chavin de Huantar and Hesiod’s description. Not only do Hesiod’s geographical descriptions fit the site, local legends also match the Greek myth, and artifacts in the temple also seem to correspond.

Geographical Similarities

Hesiod wrote of the dwelling place of the gorgons: “ … Grim and dank and loathed even by the gods—this chasm is so great that, once past the gates, one does not reach the bottom in a full year’s course, but is tossed about by stormy gales …”

Mattievich wonders if this describes the mouth of the Amazon River. Or, does it describe the length of the dangerous journey across the ocean to South America, followed by the trip up the Amazon to the gates of Pongo de Manseriche—a deep and narrow gorge that strangles the Marañon River. Dangerous whirlpools often form in the upper Marañon.