California’s State Water Resources Control Board will vote Tuesday on a proposed amendment (pdf) to current state policy on the use of coastal and estuarine waters for the ‘once-through cooling’ (OTC) of 4 gas-fired power plants due to be retired at the end of 2020.

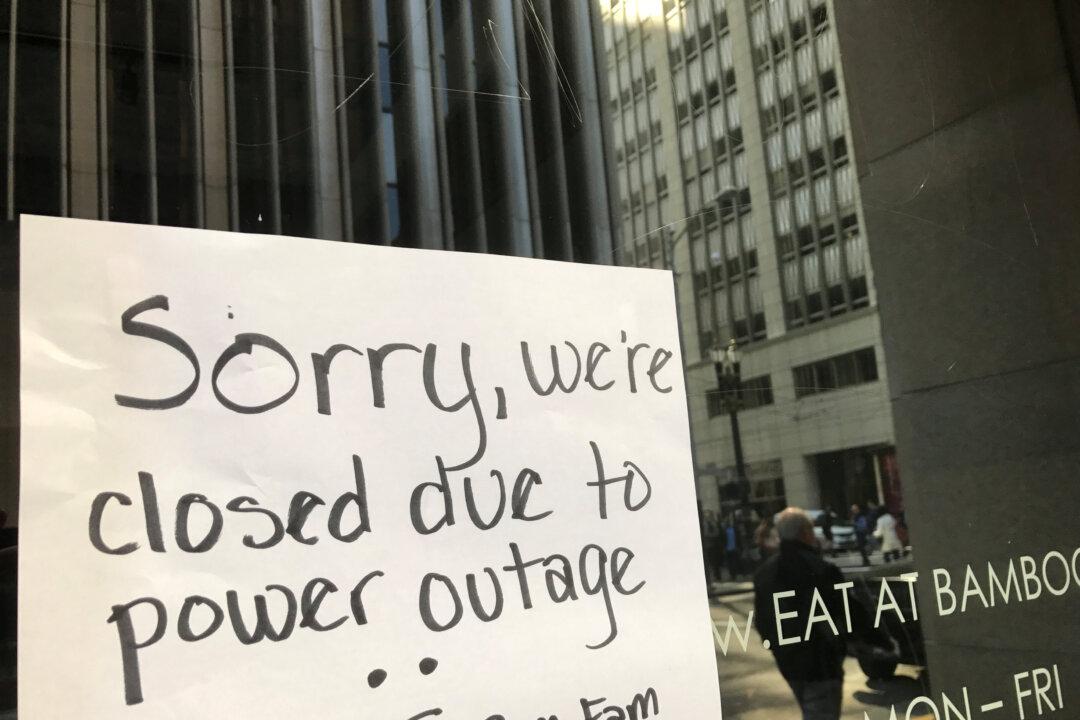

The vote comes just days after the state was crippled by rolling blackouts amid a west-coast heatwave that saw wildfires spread across thousands of acres. According to California Gov. Gavin Newsom (pdf), “These blackouts, which occurred without prior warning or enough time for preparation, are unacceptable and unbefitting of the nation’s largest and most innovative state.”