NEWARK, N.J.—When Danielle Wang and her husband arrived in Beijing late in July to meet her father, what should have been a joyful reunion was tainted with palpable anxiety and concern.

Wang Zhiwen is one of China’s most heavily persecuted political prisoners. In 1999, he was put through a show trial and handed a highly publicized 16-year prison sentence for his role as a volunteer coordinator of the Falun Gong spiritual discipline. The Communist Party’s ferocious persecution of the practice was just getting underway, and Wang’s heavy sentence was meant as a warning to the public.

Even now, Wang is watched 24/7 by Chinese plainclothes police details and a large number of undercover informants.

On a mission to bring the elder Wang to the United States, his daughter and son-in-law stepped into the web of round-the-clock surveillance and harassment.

The family secured a Chinese passport issued in January and a visa from the American consular authorities for Wang, who managed to evade scores of undercover agents and plainclothes officers. Despite these efforts, Wang was stopped by customs officers on Aug. 6, just before gaining entry to Hong Kong.

There, officers snatched his passport and clipped off a corner of the document, invalidating it. They gave no explanation, other than that it had been cancelled.

According to human rights researchers, Falun Gong practitioners have been incarcerated by the millions over the 17 years of repression. Thousands have been confirmed dead by torture in or shortly after release from custody, while ongoing investigations indicate that adherents are the primary victims of organ harvesting, a large and profitable industry.

“I think there’s really no way of imagining what China is under this communist regime unless you go there,” said Danielle’s husband Jeff Nenarella, in an interview soon after getting back from China. “I’ve been reading articles about practitioners persecuted in China for years, and it never hit me like it hit me when I went there.”

Intimidation and Harassment

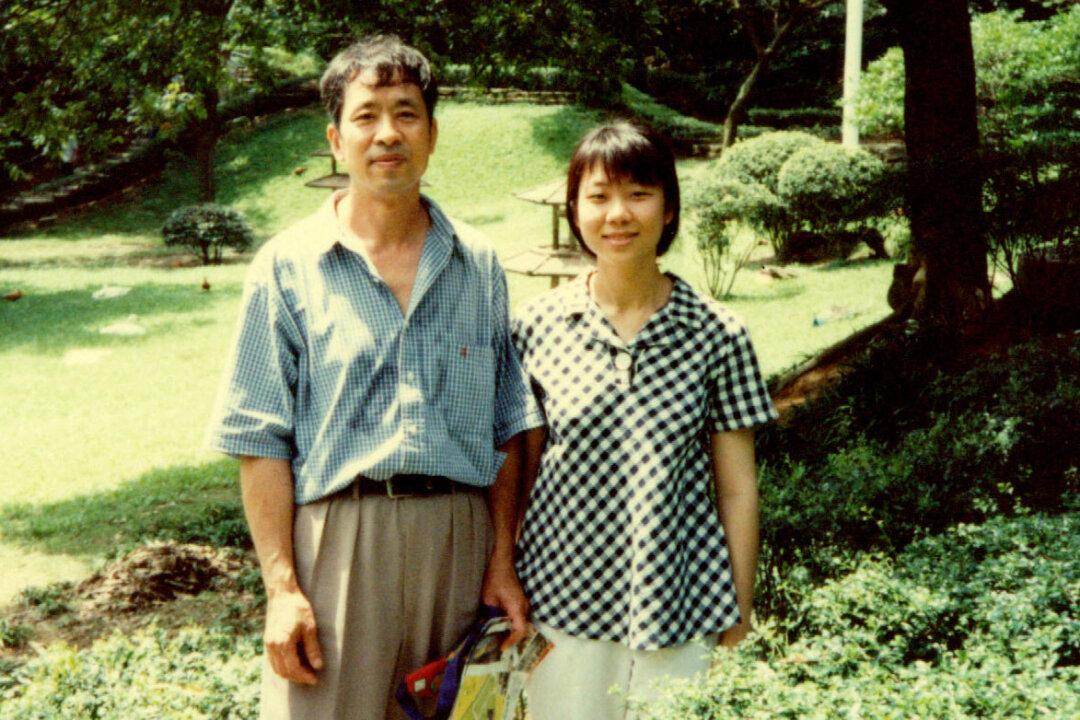

Danielle Wang (Chinese name Xiaodan Wang), who came to the United States as a student in 1998, has been struggling to obtain freedom for her father ever since he was illegally arrested on July 20, 1999, the day the Communist Party rolled out its brutal and long-standing campaign against the group.

For this trip, she and Nenarella arrived unannounced. They also risked being jailed and abused, despite their status as American citizens. Any communication with mainland China was at risk of being intercepted. The couple has been guarded about how they managed to arrange this rendezvous ahead of time.

The three left the capital for the Chinese south, where Danielle planned to collect her father’s visa from the American Consulate in Guangzhou. During the elder Wang’s exodus, his daughter fended off multiple monitors bent on keeping her father under watch.

Once out of Beijing, the three boarded a flight to Guangzhou. But that too had been fraught with interference. Days earlier, Wang’s pre-ordered ticket was inexplicably cancelled, forcing them to get one by other means. A local policeman had come to his home to question him about his purchase and to warn him not to attempt emigration.

But once they arrived in the south, Wang’s minders had traced him there, and took new measures. On the day that Danielle went to the American Consulate to get her father’s visa, three men posing as electrical maintenance workers loitered outside their rented room, trying to peer inside via the peephole.

That night, between 20 and 30 police officers pounded on the door, demanding to be let in for the ostensible purpose of confirming Nenarella’s travel papers. Over the next three days, about 10 police and agents shadowed the trio right up until they tried to enter Hong Kong, to travel on to the United States.

Still, the couple was hopeful. The fact that Wang had been able to get a passport—a document issued by the Ministry of Public Security—indicated that he would have a good chance at emigration.

This was a sea change from when Wang was in prison, sandwiched between inmates, deprived of sleep, and having toothpicks jammed under his fingernails. In the early years of his imprisonment, Wang lost his teeth from beatings; both of his collarbones were broken and not properly set. He was forced to do slave labor, and his shackles over 5o pounds. He suffered a stroke just before his release in 2014.

“This time I was really optimistic,” said Danielle upon arriving at the Newark International Airport empty handed on Aug. 9. “My father got a passport and completed all the immigration processes. I was confident I could get my father out.”

According to Wang, the customs officials who destroyed her father’s passport, and with it years of effort to rescue him, claimed the travel documents had been voided by “internal bureaus” of the Ministry of Public Security.

Who Wants to Stop Wang Zhiwen?

To Nenarella, that Wang’s passport was issued by the national authorities without incident, only to be voided and destroyed without any sort of legal rationale, points to subversion of central power.

“My understanding is that it has to be approved at the higher levels of the regime,” he said, pointing to the highly politically sensitive nature of Wang’s case.

According to Nenarella, a few months after Wang received his passport, some police came to his house and were confused as to how he obtained it.

While the Chinese Communist Party has never formally changed its stance on Falun Gong, the current leadership is locked in political struggle with the faction of Jiang Zemin, the nearly 90-year-old retired Party boss who began the persecution and used it as an opportunity to push his own lieutenants into positions of power.

As many of these formerly made men fall in the anti-corruption campaign led by current Chinese regime leader Xi Jinping (a man with no career investment in suppressing Falun Gong), there have been many indications that Party Central has lost interest in the spiritual practice. But persecution continues on the back burner.

Danielle Wang is still determined to reunite with her father.

“This experience has steeled my determination to tell my father’s story to people around the world, to governments and the media, until he can be rescued.”

Their brief, bittersweet reunion began much as it had started: with the father’s concern for his family’s safety. The day after customs turned him away, he saw the couple off as they left for North America.

“He didn’t tell me where he would go from here,” Danielle said. “I’ve lost him again.”

Danielle Wang has started a petition on Care2 addressed to Secretary of State John Kerry, asking him to pressure the Chinese Communist Party to reissue her father’s passport and allow him to travel abroad.