Airbus is planning to test new radar that would detect volcanic ash particles released in the air. Ash spewed by active volcanoes is destructive to airplanes and can even cause a plane to nose-dive and fall from the skies.

Eruptions from the Eyjafjallajökull volcano in April this year and the consequent disruption of the air traffic over the North Atlantic and Europe prompted airline authorities to search for a swift solution to this problem. They needed to determine how much ash an engine can ‘inhale’ without risking damage or passenger safety, and test the airspace for a concentration of particulates.

The Airborne Volcanic Object Identifier and Detector (VOID) may be the answer. While volcanic ash is invisible to other radar technologies, VOID uses infrared technology to find and relay readings of destructive volcanic ash to pilots and ground control.

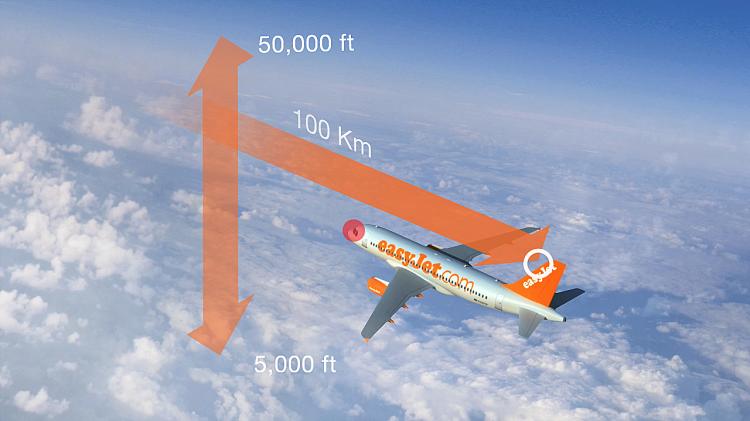

VOID detects and frames ash clouds from a distance of up to 60 miles ahead of the aircraft at altitudes between 5,000 feet and 50,000 feet. The system would be mounted on the airplane’s vertical stabilizer—part of the fuselage—and is in essence similar to weather radar.

The tests of the new infrared radar are slated to be complete in two months. The largest U.K. airline company, easyJet, would supply its fleet with the new infrared technology if the initial tests prove the radar’s efficacy. The new system is created by Dr. Fred Prata of the Norwegian Institute for Air Research.

British Airways Flight 9 in 1982 and the KLM Flight 867 in 1989 both experienced the harmful effects caused by volcanic ash. In these incidents the aircrafts entered airspace with dense ash clouds, jamming the engines. Luckily, following certain restart procedures the crews of both aircrafts were able to bring their engines back on power and land safely.

However, an investigation of Flight 9 revealed that the airplane fuselage and engines experienced damage from flying in volcanic ash clouds.

Ash clouds consist of small yet hard mineral particles which hit the metal fuselage of the airplane, creating friction and an abrasive effect. Such particles can rapidly cause significant wear on the propellers or on the blades of the jet’s engine.

Once ‘inhaled’ by the engine, ash particles melt in the combustion chamber depositing molten ceramic substances that stick inside and cause the engine to choke and fail. Prolonged exposure to a concentration of these particulates can bring engines to a halt and stop the energy supply which is vital for the airplane’s navigational controls.

Severely decreased visibility caused by particles hitting the windshields at an average speed of 500 mph is another destructive effect of the ash, and can prevent pilots from seeing runways or other landing marking, especially at night.

This year’s Eyjafjallajökull eruptions caused a staggering $3 billion loss to the airline companies. The United States Geological Survey reports that there are currently 169 active volcanoes in the United States.

Eruptions from the Eyjafjallajökull volcano in April this year and the consequent disruption of the air traffic over the North Atlantic and Europe prompted airline authorities to search for a swift solution to this problem. They needed to determine how much ash an engine can ‘inhale’ without risking damage or passenger safety, and test the airspace for a concentration of particulates.

The Airborne Volcanic Object Identifier and Detector (VOID) may be the answer. While volcanic ash is invisible to other radar technologies, VOID uses infrared technology to find and relay readings of destructive volcanic ash to pilots and ground control.

VOID detects and frames ash clouds from a distance of up to 60 miles ahead of the aircraft at altitudes between 5,000 feet and 50,000 feet. The system would be mounted on the airplane’s vertical stabilizer—part of the fuselage—and is in essence similar to weather radar.

The tests of the new infrared radar are slated to be complete in two months. The largest U.K. airline company, easyJet, would supply its fleet with the new infrared technology if the initial tests prove the radar’s efficacy. The new system is created by Dr. Fred Prata of the Norwegian Institute for Air Research.

British Airways Flight 9 in 1982 and the KLM Flight 867 in 1989 both experienced the harmful effects caused by volcanic ash. In these incidents the aircrafts entered airspace with dense ash clouds, jamming the engines. Luckily, following certain restart procedures the crews of both aircrafts were able to bring their engines back on power and land safely.

However, an investigation of Flight 9 revealed that the airplane fuselage and engines experienced damage from flying in volcanic ash clouds.

Ash clouds consist of small yet hard mineral particles which hit the metal fuselage of the airplane, creating friction and an abrasive effect. Such particles can rapidly cause significant wear on the propellers or on the blades of the jet’s engine.

Once ‘inhaled’ by the engine, ash particles melt in the combustion chamber depositing molten ceramic substances that stick inside and cause the engine to choke and fail. Prolonged exposure to a concentration of these particulates can bring engines to a halt and stop the energy supply which is vital for the airplane’s navigational controls.

Severely decreased visibility caused by particles hitting the windshields at an average speed of 500 mph is another destructive effect of the ash, and can prevent pilots from seeing runways or other landing marking, especially at night.

This year’s Eyjafjallajökull eruptions caused a staggering $3 billion loss to the airline companies. The United States Geological Survey reports that there are currently 169 active volcanoes in the United States.