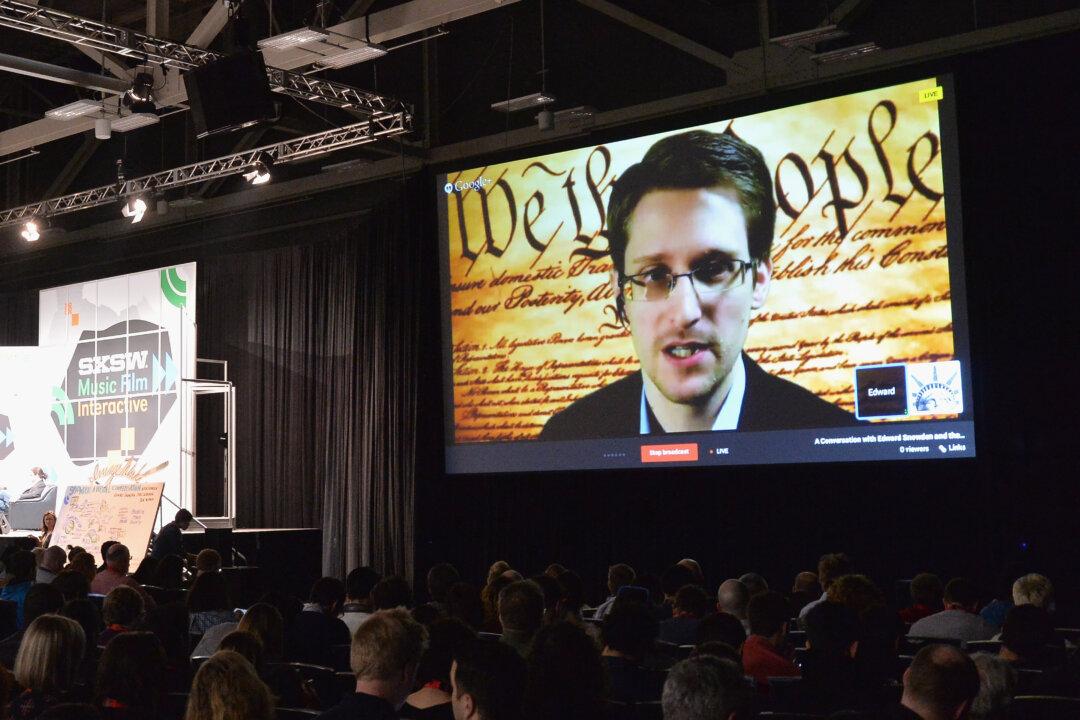

After former NSA contractor Edward Snowden stole and released documents about spying activities of the NSA, the world got a glimpse of the war on the wires. Yet, after the mask over global espionage was pulled off, intelligence agencies in China and Eastern Europe significantly increased their operations of spying and theft.

Experts in counterintelligence said they witnessed a fivefold increase in physical espionage attempts against U.S. businesses. A similar trend took place with cyberespionage, where a recent Verizon report said there was a threefold increase.

“Right or wrong, Snowden has caused other nation-states to increase their activity, and their brazenness,” said Casey Fleming, CEO of BlackOps Partners Corporation, which does counterintelligence and protection of trade secrets and competitive advantage for Fortune 500 companies.

Since the event, Fleming said he has seen a fivefold increase in both cyberespionage and insider espionage attempts against the major U.S. businesses that his company advises.

Verizon recorded similar findings in its “2014 Data Breach Investigations Report.” It found a 300 percent increase in espionage incidents in 2013 from the previous year.

Verizon recorded 511 espionage incidents, 306 of which were successful. Among the attacks, it states that 49 percent came from “Eastern Asia,” which refers principally to China and North Korea. The report from the previous year stated that 96 percent of espionage incidents came from China.

The United States was by far the largest target of cyberespionage, being hit with 87 percent of espionage incidents, according to the report. South Korea was second, being targeted by 6 percent of attacks.

The Snowden Effect

Fleming noted that while Snowden exposed espionage conducted by the United States and its allies, he also created an environment of blanket acceptance for espionage by other nations.

Snowden gave other countries an excuse to pay less attention to being caught, since the “You do it too” or the “We’re just trying to keep up” lines can now be conveniently used by any adversary.

China, for example, is currently using information leaked by Snowden in an attempt to justify and draw equivalence between U.S. spying and its own use of espionage for economic theft.

The FBI and Department of Justice unsealed charges against five officers of the Chinese army on May 19, alleging they were directly involved in China’s state-run theft of intellectual property from U.S. businesses.

The response from China included a report from its Internet Media Research Center on May 27, accusing the United States of spying. The report is built almost entirely from information on U.S. spying leaked by Snowden, yet includes no evidence of U.S. spying for economic theft.

Rising Threats

The recent charges unsealed against China’s military hackers are part of an effort by U.S. officials to draw lines distinguishing what is acceptable and unacceptable in the realm of espionage. The Chinese regime crossed the line, they said, by using espionage as a tool to steal from U.S. businesses to feed its own economy.

The Chinese officers are from Unit 61398 of the Third Department of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army. The unit and its use of cyberespionage were exposed in February 2013 by security company Mandiant.

A recent report from Mandiant noted that the unit went dormant after it was exposed, but increased the scale of its operations after it re-emerged. The report states that in 40 percent of attacks, Chinese hackers in general continued their operations even after being caught.

According to Laura Galante, manager of threat intelligence at FireEye Labs, it is less likely China’s military hackers will go dormant this time around. FireEye monitors large-scale cyberespionage campaigns, including the activities of several major hacker groups in China.

“From our vantage point and looking at mostly Fortune 500 companies, I can’t imagine the amount we’re seeing could be turned off quickly or easily,” Galante said.

She said the Chinese regime has been launching these types of large-scale cyberattacks for close to a decade, and “simply because of wanted posters from the Department of Justice, they’re not going to turn off these state-sponsored attacks at least in terms of volume.”

Galante said cyberespionage campaigns from China have been increasing, and while Snowden has made the topic of espionage difficult for the United States to talk about, it’s uncertain whether the scale of China’s attacks would be any different if it weren’t for Snowden.

The problem with China, she said, is that many of its state-run enterprises rely on theft through cyberespionage for their research and development. She noted China “can’t siphon off its R&D collective when it’s that dependent on it.”