The Assembly of First Nations has added its voice to the chorus of calls for a public inquiry into the handling of the Robert Pickton investigation.

AFN Chief Shawn Atleo said an inquiry is necessary in order seek justice for the 20 women—some of whom were aboriginal—who lost their lives at Pickton’s hands, but have not had their cases tried.

“Many of these victims were First Nations and aboriginal women and a full and comprehensive public inquiry, with the participation of Aboriginal people, is the only way to address the need for respect, justice, and a better understanding of how we can prevent these tragedies in the future,” Atleo said in a statement.

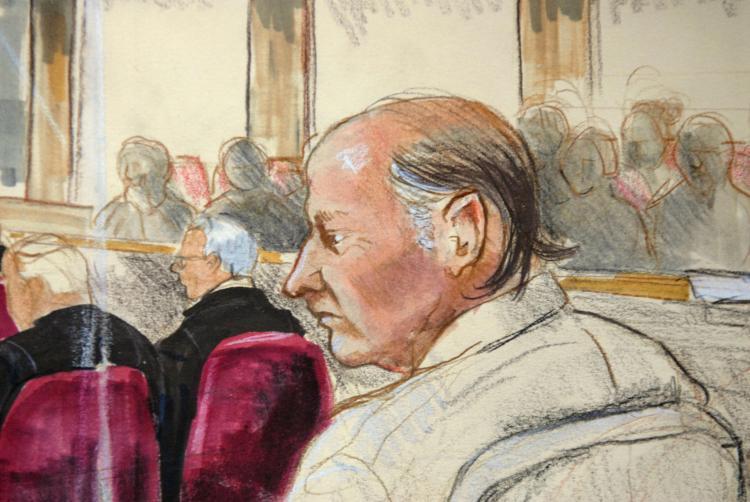

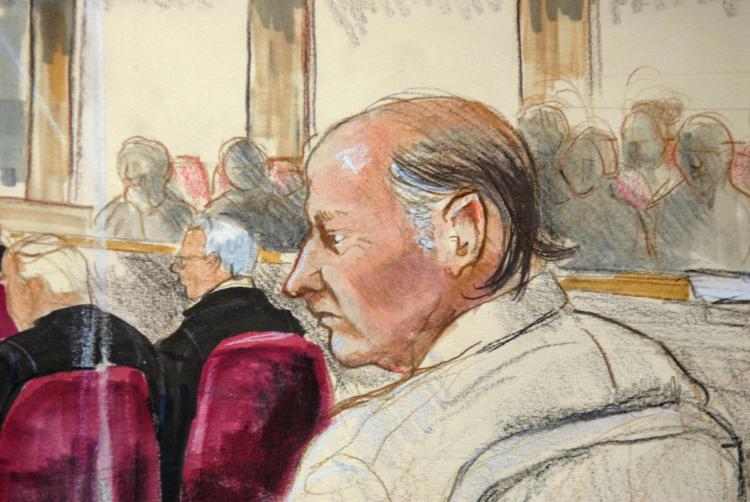

Pickton, 60, was convicted in 2007 of second-degree murder in six deaths, for which he received life in prison with no possibility of parole for 25 years.

Calls for a public inquiry grew after charges of first-degree murder in the deaths of another 20 women were stayed and publication bans were lifted.

B.C. Crown spokesman Neil MacKenzie said at a press conference on July 30 that “any additional convictions could not result in any increase to the sentence that Mr. Pickton has already received.”

Groups including the Vancouver Police Department, the RCMP, Vancouver Mayor Gregor Robertson, B.C. Civil Liberties Association, Amnesty International Canada, and some of the families of the victims, all want a public inquiry into how the case was handled by police.

“Some are saying that the cost of an inquiry would be too high,” Atleo said. “We say that you cannot put a value on a human life. The benefits of closure and prevention that will result from an inquiry outweigh any other costs.”

B.C. Premier Gordon Campbell said Aug. 5 that his cabinet will decide in the coming weeks whether to call a public inquiry.

The Port Coquitlam pig farmer first became a suspect in 1998 when the Vancouver police received information from Bill Hiscox, who used to work for Pickton. At the time, a woman who cleaned Pickton’s trailer told Hiscox that she had seen bags of bloody clothing and women’s identification in the trailer.

However, it was another 3 1/2 years before Pickton was arrested, during which time over 20 women disappeared from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

“Twenty-two of those women would still be alive today if they would have listened to me in 1998,” Hiscox told CBC News. “I mean, what did they take me for, some kind of an idiot or what? I just don’t understand that.”

At the July 30 press conference, Deputy Chief Const. Doug LePard apologized to the victims’ families “from the bottom of my heart.”

“I wish that all the mistakes that were made we could undo and I wish more lives would have been saved,” he said.

“So on my behalf and [on] behalf of the Vancouver police department ... I would say to the families how sorry we all are for your losses and because we did not catch the monster sooner.”

AFN Chief Shawn Atleo said an inquiry is necessary in order seek justice for the 20 women—some of whom were aboriginal—who lost their lives at Pickton’s hands, but have not had their cases tried.

“Many of these victims were First Nations and aboriginal women and a full and comprehensive public inquiry, with the participation of Aboriginal people, is the only way to address the need for respect, justice, and a better understanding of how we can prevent these tragedies in the future,” Atleo said in a statement.

Pickton, 60, was convicted in 2007 of second-degree murder in six deaths, for which he received life in prison with no possibility of parole for 25 years.

Calls for a public inquiry grew after charges of first-degree murder in the deaths of another 20 women were stayed and publication bans were lifted.

B.C. Crown spokesman Neil MacKenzie said at a press conference on July 30 that “any additional convictions could not result in any increase to the sentence that Mr. Pickton has already received.”

Groups including the Vancouver Police Department, the RCMP, Vancouver Mayor Gregor Robertson, B.C. Civil Liberties Association, Amnesty International Canada, and some of the families of the victims, all want a public inquiry into how the case was handled by police.

“Some are saying that the cost of an inquiry would be too high,” Atleo said. “We say that you cannot put a value on a human life. The benefits of closure and prevention that will result from an inquiry outweigh any other costs.”

B.C. Premier Gordon Campbell said Aug. 5 that his cabinet will decide in the coming weeks whether to call a public inquiry.

The Port Coquitlam pig farmer first became a suspect in 1998 when the Vancouver police received information from Bill Hiscox, who used to work for Pickton. At the time, a woman who cleaned Pickton’s trailer told Hiscox that she had seen bags of bloody clothing and women’s identification in the trailer.

However, it was another 3 1/2 years before Pickton was arrested, during which time over 20 women disappeared from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

“Twenty-two of those women would still be alive today if they would have listened to me in 1998,” Hiscox told CBC News. “I mean, what did they take me for, some kind of an idiot or what? I just don’t understand that.”

At the July 30 press conference, Deputy Chief Const. Doug LePard apologized to the victims’ families “from the bottom of my heart.”

“I wish that all the mistakes that were made we could undo and I wish more lives would have been saved,” he said.

“So on my behalf and [on] behalf of the Vancouver police department ... I would say to the families how sorry we all are for your losses and because we did not catch the monster sooner.”