Wild geese are migratory birds that travel great distances along well-defined routes every year between their breeding grounds in the north and wintering grounds in the south.

Taking advantage of their natural instinct to follow the change of seasons in their annual north-south journey, the ancient Chinese used these faithful birds to carry messages by attaching small scrolls to their feet.

With this practice, the wild goose, 鴻雁 (hóng yàn) or 雁 (yàn), came to symbolize a letter or an exchange of correspondence in Chinese, and the idiom 鴻雁傳書 (hóng yàn chuán shū), literally “a wild goose delivers a message,” vividly depicts the use of these birds as messengers.

One of the most famous stories associated with this idiom is that of Su Wu (蘇武), a loyal envoy sent on a diplomatic mission to the Xiongnu (匈奴) in 100 B.C. by Emperor Wu (漢武帝) during the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.–A.D. 220).

The Xiongnu, long-time invaders of China, tried to force Su Wu to surrender. When he refused, they banished him to a remote, desolate location to herd sheep until “your rams give milk.”

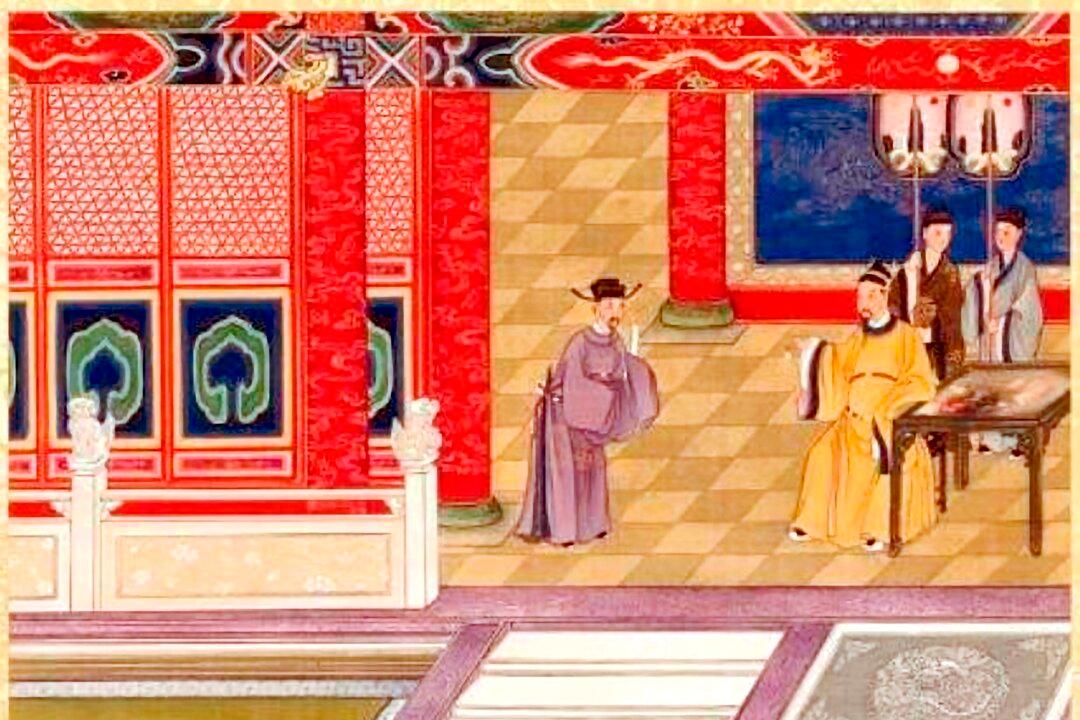

In 81 B.C., as part of peace negotiations between the two sides, a Han envoy was sent to the Xiongnu to seek Su Wu’s return.

The Xiongnu tried to deceive the envoy by saying that Su Wu had already died. However, the envoy learned the truth from a member of Su Wu’s original delegation.

The man advised the envoy to tell the Xiongnu king that the Han emperor had recently shot down a goose while hunting and found a piece of cloth attached to the goose’s feet with writing that said Su Wu and others of his delegation were detained in a certain location by a lake.

Shocked to hear these words, the Xiongnu king admitted that Su Wu and the others were indeed there.

Thus, Su Wu and his companions were finally released and returned to China, after 19 years of captivity.