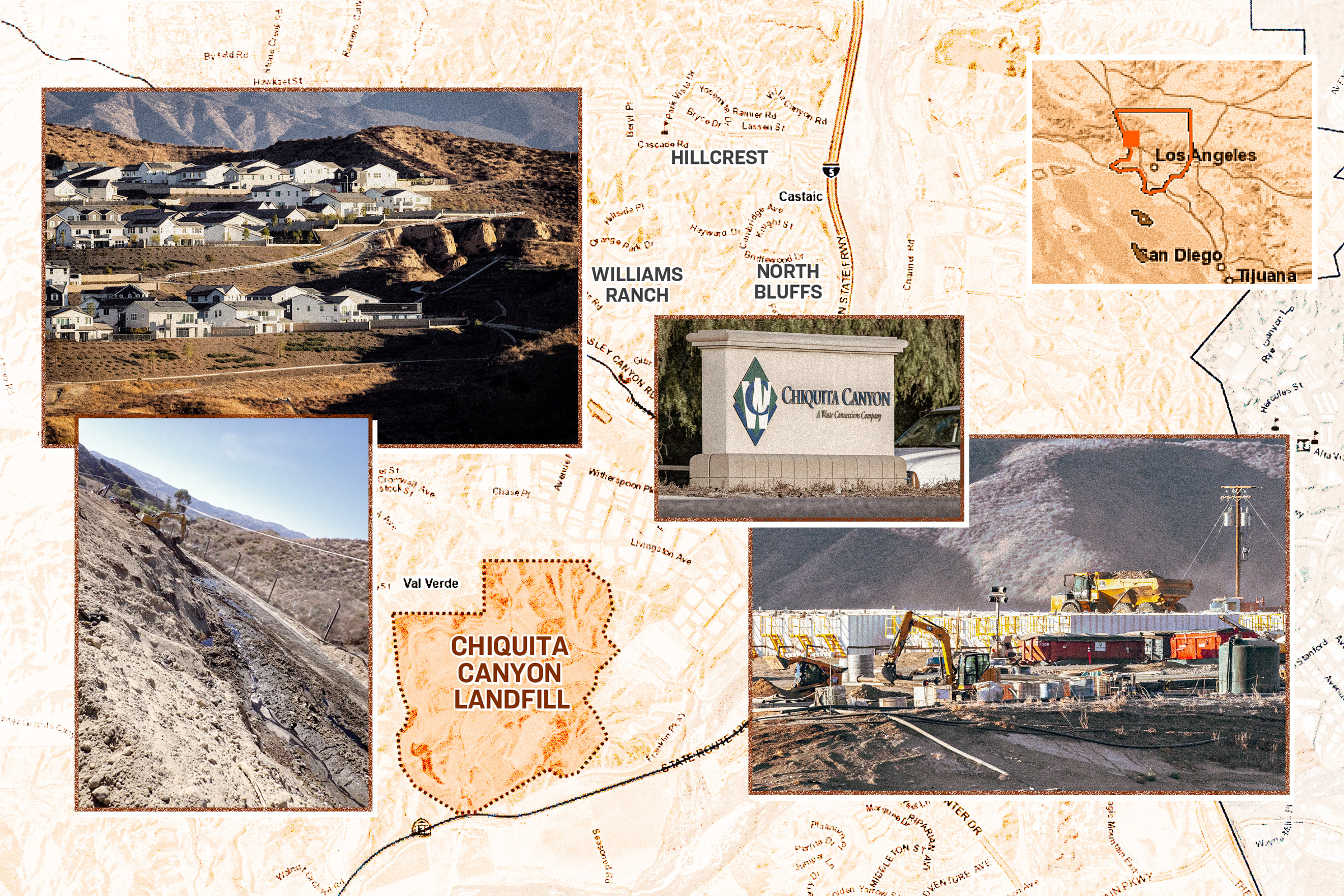

LOS ANGELES—When Romeo Centeño moved his family to Val Verde 14 years ago, he was drawn to the tranquility of the area—a hamlet in the hills at the northwestern edge of Los Angeles County, about 50 miles north of downtown Los Angeles. It was a safe place to raise his children, then 10 and 14.

“This is such a great area,” Centeño told The Epoch Times. “It is a quiet, rural area where you can still see deer all over the place, you see rabbits, all kinds of wild animals. It’s such a beautiful place.”