Over the past seven years—while controversy raged over the Keystone XL pipeline—many newly approved oil pipelines were built, and old ones “repurposed” nationwide—with little public knowledge or opposition. Some transport the same gummy, highly polluting tar sands oil, or bitumen, that Keystone was slated to carry.

During this same 2008 to 2015 period, a record number of pipeline accidents poisoned land, polluted waterways, and exploded.

Some leaks were small. Others were massive, like the 2010 rupture of Enbridge Energy’s Line B pipeline in Marshall, Michigan, the largest, costliest onshore oil spill in U.S. history. It spewed 843,000 gallons of tar sands oil into a field and the Kalamazoo River. Some 40 miles of river remained closed for years because, unlike conventional crude, the heavy bitumen sinks, making cleanup difficult. So far, it’s cost $1.2 billion.

Two years ago, a 22-foot gash in ExxonMobil’s 65-year-old Pegasus pipeline engulfed a Mayflower, Arkansas, neighborhood in 210,000 gallons of bitumen that also flowed into nearby Lake Conway.

Other ExxonMobil pipeline spills dumped 117,000 gallons of oil into a coastal waterway near Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 2012 and fouled Montana’s pristine Yellowstone River twice, with 63,000 gallons in 2011 and 30,000 gallons this year. Sunoco’s Mid-Valley Pipeline running from Texas to Michigan has seen 40 “incidents” since 2006.

More than 100 significant spills occur yearly. But hundreds of cracks and breaks occur along the 2.5 million miles of pipeline that carry oil, propane, and natural gas across major rivers, beneath cities, suburbs, farms, forests—and near shallow aquifers.

Accidents occur because aging pipelines are deteriorating. Weak welds give way, construction crews dig in the wrong place, and natural disasters hit. Bitumen puts greater stress on pipes: It’s so thick that it must be pumped at high heat and high pressure.

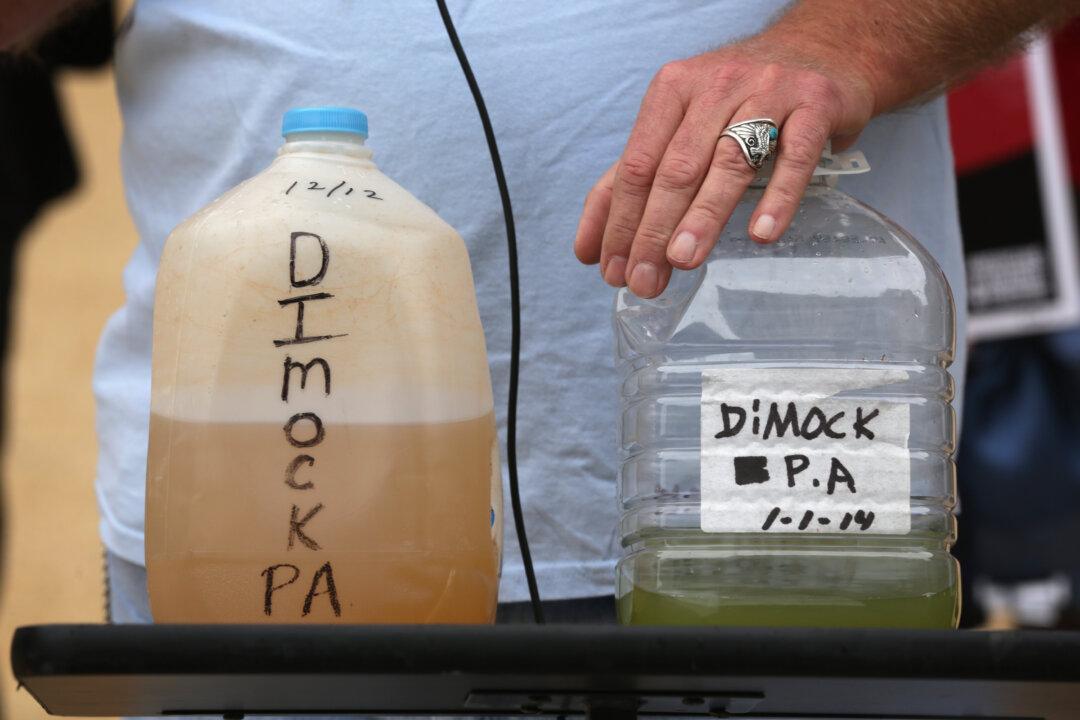

Oil spills contaminate waterways and land, kill wildlife, and sicken people. A spill envelops its surroundings in caustic petrochemical fumes from volatile organic chemicals, toluene, benzene (a known carcinogen), and more. Viscous tar sands oil is even more toxic, since it must be thinned with any of 1,000 chemicals to make it flow through a pipe.

Citizens who live near both the Michigan and Arkansas spills reported similar symptoms: they vomited, had intestinal problems, and gasped for breath; suffered from exhaustion, migraines, dizzy spells, confusion and nosebleeds; and developed skin rashes that resembled chemical burns. Research shows that even infinitesimal doses of some petrochemicals can have serious health effects. Children are particularly at risk.

To meet the current oil boom—and skirt federal approvals and environmental impact studies—many corporations are repurposing antiquated pipelines rather than constructing new ones. Half are at least 45 years old and not built to current standards. Companies are running oil through lines built for natural gas and pushing thick bitumen through pipes constructed for conventional oil, carrying heavier loads at higher pressure.

If wrapped around the equator, U.S. pipelines would circle the Earth more than 100 times. Federal regulators checked just one-fifth of them from 2006 to 2013. The agency tasked with oversight, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) currently has just 139 inspectors—not enough.

From 2009 to 2013, the agency’s staff spent far more time with the petroleum industry than in the field, according to research by the Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER). Personnel spent three times as many days attending 850 industry meetings and events as they did investigating 159 spills, and failed to scrutinize over 300 spills and explosions.

PEER found that the fox is guarding the henhouse. Not only do companies self-monitor the safety of their own pipelines, but PHMSA had no record of reviewing that inspection data.

Companies also write their own emergency response plans, none of which were revised or rejected by government experts during that same 2009–2013 period. The industry dictates its own pipeline routes, which means multiple lines often converge, raising risks for residents living near junctions.

PHMSA—a critical safety agency—needs to remedy its dereliction of duty. To their credit, federal regulators have proposed the Hazardous Liquids Integrity Verification Process, with broad changes to oil pipeline safety rules. The oil and pipeline industries have launched heavy lobbying efforts against it—but it must be approved.

However, as climate change gallops on, we need to focus on a larger goal than pipeline safety and a careless industry. We must swiftly wean the nation off fossil fuels—before we ravage all life on Earth.

Sharon Guynup is co-author (with Steve Winter) of “Tiger’s Forever: Saving the World’s Most Endangered Big Cat” and is a frequent Blue Ridge Press contributor. © www.blueridgepress.com 2015.