Preet Bharara, the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, made front-page news in December when he booked an obscure Indian diplomat—deputy consul general Devyani Khobragade—for underpaying her maid. The foreign policy headache from the arrest ended when Khobragade left the country, but the more serious domestic hazard remains: that of the expanding latitude of U.S. attorneys in battling crime, which too often results in unchecked power that jeopardizes the public good.

The number of offenses classified as crimes in federal statutes has grown enormously from a few dozen at the turn of the twentieth century to several thousand today. Some of the expansion was warranted by new forms of criminality. International mobsters and terrorists, child pornography on the Internet, income-tax evasion, and Medicare fraud didn’t exist in 1790, when the first criminal statute was signed into law.

Unfortunately, busybody Congresses have also criminalized acts whose harm is far less clear. “Individual citizen behavior now potentially subject to federal criminal control has increased in astonishing proportions,” as an American Bar Association report put it. Many crimes on the books now are not well-defined, and prosecutors often don’t have to show criminal intent to secure convictions. False statements or denials to a federal agent—uttering a simple “no” will do—now count as crimes, too, even if the underlying offense isn’t criminal.

Federal prisons and courts are strained to their limits, and American society could not long function if we convicted and imprisoned the perpetrators of all acts now deemed criminal. If our drug laws were fully enforced, for example, the current president and his two predecessors would be convicted felons. If we were as serious about unreported income as, say, Norway or Sweden have proved to be, Timothy Geithner wouldn’t have served as Treasury secretary. And so on.

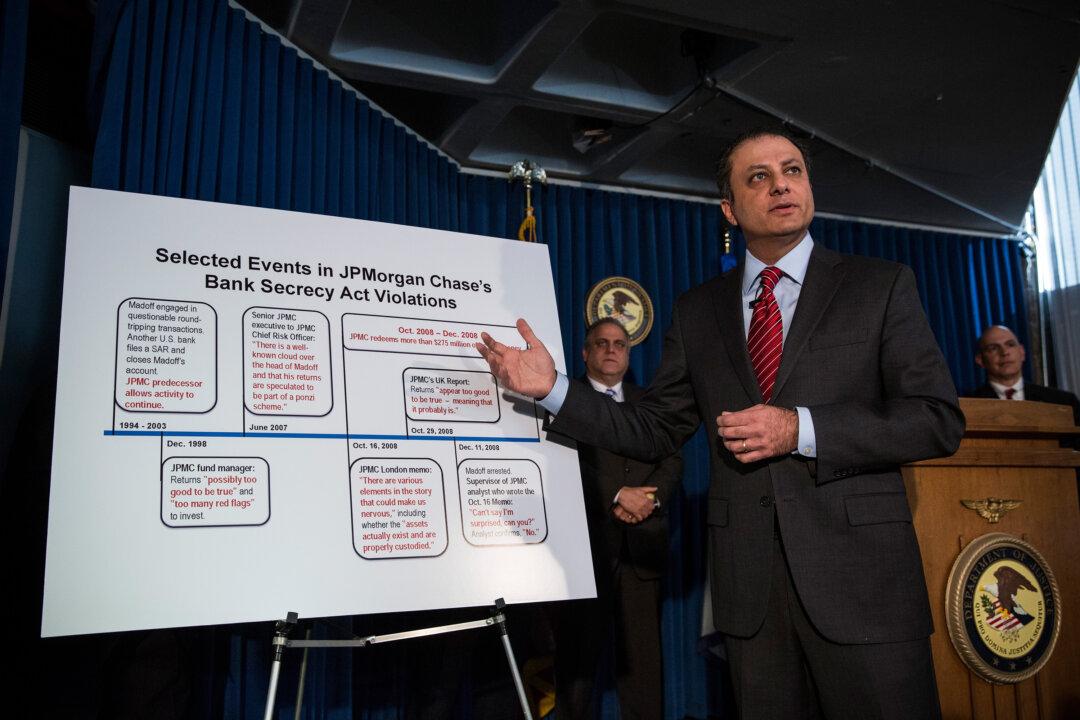

Bharara’s law-and-order battles against terrorists, criminal networks, and drug traffickers have surely advanced the public good. But it was his insider-trading convictions that got the prosecutor on a Time cover with the headline, THIS MAN IS BUSTING WALL STREET. Bharara has secured more than 70 convictions and pioneered the use of wiretaps—traditionally used against organized crime—to catch insider traders.

The harm of insider trading turns on contestable economic theory rather than a serious observable injury. As I have long argued, insider-trading laws promote excessive trading and liquidity and undermine good corporate governance. In any case, promoting speculative capitalism seems hardly worth full-tilt criminal prosecution—especially when top executives of banks that have admitted to the outright fraud at the heart of the 2008 financial collapse have escaped prosecution.

The Case of the Maid

The arrest (and alleged strip-search) of Khobragade was particularly puzzling. She’s accused of paying her live-in maid a below-minimum-wage salary of $500 per month. Assuming that the allegation is true, is the harm punished or deterred commensurate with the costs of the prosecution? No U.S. citizens—the presumed beneficiaries of minimum-wage laws—were underpaid or potentially deprived of a job paying legal wages. Khobragade couldn’t have paid the minimum wage on her $4,180 monthly salary. The maid was not imprisoned or abused. And while $500 a month for live-in help might seem scandalously low to a New Yorker, it’s several times what the maid would have earned in India.

Now suppose an all-out campaign against diplomatic scofflaws halts the import of low-cost maids: this would hardly be a boon to those deprived of a once-in-a-lifetime employment opportunity in the United States. Or perhaps the Indian government will increase allowances to its diplomats so that they can pay their maids higher wages.

But what moral advantage does a transfer from impoverished Indian taxpayers to a few lucky maids provide? In a New York Times op-ed, Ananya Bhattacharyya portrayed Indian outrage at its consul’s arrest as complicity in an exploitative system. Chances are that she composed her column at a computer assembled by workers paid a lower wage than the maid and toiling under harsher conditions. Yet she presumably does not regard herself as complicit in exploitation of sweatshop labor.

The political costs of such overreach aren’t trivial. The arrest damaged relations with a generally friendly Indian public and government. Asserting the unqualified primacy of domestic laws can jeopardize the safety of our diplomats. U.S. embassies in India and elsewhere are often shielded by protective barriers that could be removed because they were erected in violation of the local rules, for instance. Scarce prosecutorial, judicial, and diplomatic resources are consumed in such episodes. Replicating witness-protection programs for Mafia informants, the maid’s family was preemptively spirited out of India, supposedly to protect against retribution and brought to the United States—at considerable cost to American taxpayers.

These circumstances are unusual but the general problem is not. Congress has greatly expanded the discretion of unelected federal officials. Whether one agrees or disagrees with this mandate, all should be alarmed by the absence of a commensurate increase in accountability or oversight. Thus we can debate whether an audacious monetary experiment, “quantitative easing,” is worthwhile; that it can be undertaken by twelve unelected members of the Federal Open Market Committee, without any Congressional review, undermines the checks and balances so foundational to our democracy. In the argot of modern economics, good governance, even in large private organizations, requires separation of management and control.

Expanded prosecutorial discretion rarely gets as much attention as abuses by the Fed or the NSA, but the problem of unchecked power is no less acute. Federal prosecutors, unlike their state counterparts, remain unanswerable to voters. Their decisions can technically be contested on grounds of selective prosecution or vindictiveness, but such challenges are difficult to sustain. Department of Justice guidelines place few practical constraints on the charges prosecutors can press.

A legal code that criminalizes so much that isn’t blatantly criminal must also require more independent ratification and review of prosecutorial choices by the Justice Department or by Congress. U.S. attorneys should not be a law unto themselves.

Amar Bhide is Thomas Schmidheiny Professor at Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, a founding member of the Center on Capitalism and Society, and author of “A Call for Judgment: Sensible Finance for a Dynamic Economy.” This article originally appeared on the Manhattan Institute’s City Journal magazine website.