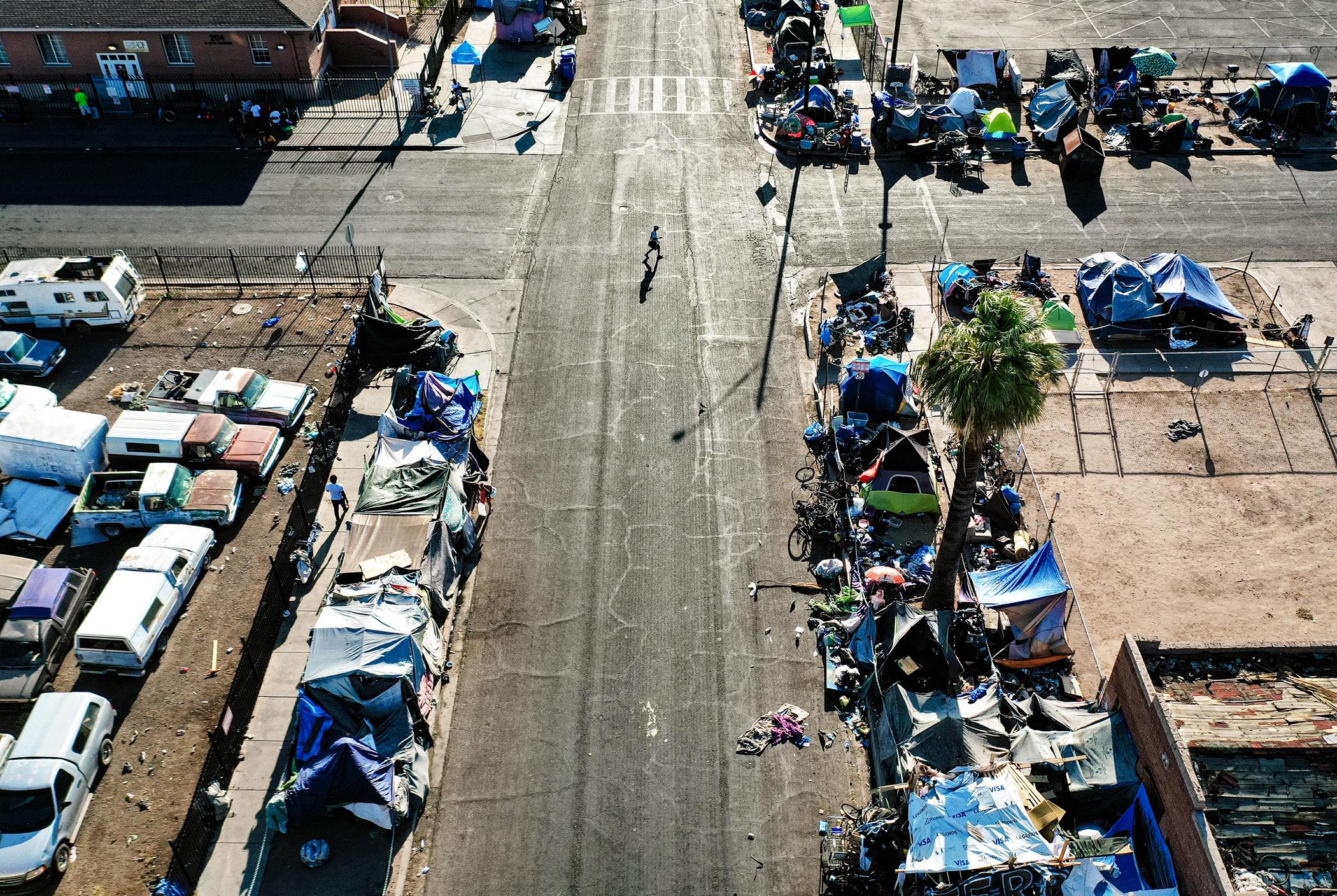

PHOENIX—The rising sun was getting dangerously hot as another day of 105-plus degree Fahrenheit heat was about to break in southern Arizona in the middle of July.

Bruce, 33, was homeless, shirtless, and wearing cargo shorts and sneakers when an Epoch Times reporter found him sitting against a building on South 11th Avenue in Phoenix.

He had been desperately seeking relief in the cool spray of a patio mister; the thought of dying from heat exposure was a constant reminder of how precarious his life had become.

“This is the worst summer we’ve had so far,” Bruce said, his tattooed upper body dripping with sweat. He said survival was a simple calculus: stay close to social services, drink plenty of water, and live to see the sun go down.

His brother, Victor, had done the math but wasn’t so lucky. He died from heat exhaustion not long ago, Bruce told The Epoch Times.

“He was like me—living on the streets,” Bruce said. “I’ve been homeless for 15 years.”

Victor, like his brother, was known to the system. His family still cared about him, so they made sure he got a proper burial when the time came.

However, it’s a different story for homeless people sweltering in the sauna-like heat who die without money, identification, or next of kin.

When this happens, the county will do everything it can to determine the deceased person’s identity and locate any family members to claim the body, according to the Maricopa County Indigent Decedent Program.

Yet when this fails, the county will reach out to local mortuaries to bury the decedent’s unclaimed remains in White Tanks Cemetery in Goodyear, 25 miles west of Phoenix.

The county-run cemetery, coined by some as Maricopa’s “Potter’s field,” opened in 1994. It is the final resting place of more than 7,000 poor and homeless souls, a number that grows with every summer heat wave.

In 2023, the county buried 482 people in the cemetery and interred 230 more during the first six months of this year.

All grave sites receive the decedent’s cremated remains for burial during a weekly service held every Thursday.

Each burial plot has a brick marker inscribed with the person’s name and date of death.

For some, the inscription reads, “Unknown.”

In a remote corner of the cemetery, a solitary brick marks the grave of “Unknown Baby Boy.” A faded pink teddy bear lies beside it in 111-degree F heat to signify a life lived briefly and lost.

The top temperature for the day reached 118 degrees F—deadly for those living without shelter.

One homeless death is a tragedy, observed John Delaney, executive director of Andre House of Hospitality in Phoenix.

He said it’s even worse when it’s someone you once knew and tried to help out of poverty, addiction, homelessness, and despair.

“It’s always sad when our guests pass away—regardless of how they pass away,” Delaney told The Epoch Times.

“The biggest thing that we’ve seen has definitely been the hot weather. It has taken a toll on our guests more than anything else recently.”

Among the nation’s most vulnerable are thousands of homeless people who are at an increased risk of dying from extreme heat exposure during the summer months.

As of July 17, there were 23 confirmed deaths due to heat exposure in Maricopa County, and 322 are still under investigation by the Department of Health.

In 2023, the department confirmed a record 645 heat-related deaths, a 52-percent spike from 2022.

Forty-five percent of the deceased in 2023 were people “experiencing homelessness.”

‘It’s Never Easy’

Delaney said that since 1984, Andre House has been a significant provider of transitional services in the metro Phoenix area, meeting the growing need among the homeless population.The mission outreach works closely with the county to ensure that each deceased homeless person receives a decent burial overseen by a volunteer chaplain.

“I think, realistically, many people that pass away from the heat do go to White Tanks Cemetery,” Delaney said.

On the night before Thanksgiving, organization volunteers conduct a prayer vigil to remember all the poor and homeless people who died that year.

Delaney said the service includes a red rose placed beside every grave marker.

“Our guests are our family. We form deep personal bonds with our guests. So, when a guest passes away, it feels personal. We’ve lost a friend,” he said.

“When children pass away, those are the hardest to deal with. The few times I’ve been to the cemetery to do the burials, I’ve had a baby one or two times. It’s never easy.”

Not every homeless person has a substance abuse problem or mental health issue, Delaney said. Many fall into poverty and homelessness through no fault of their own or through unfortunate circumstances, including sudden job loss.

As homelessness spreads throughout Phoenix and other heavily populated areas across the country, the threat of a lonely death on the streets follows the homeless population like a shadow.

The figure represents a 12.1 percent year-over-year increase among all homeless categories. It is also the highest number of homeless people recorded on a single night since reporting began in 2007.

The National Health Care for the Homeless Council (NHCHC) identified 68 cities and counties in the United States with a combined reported homeless death count of 5,807 people in 2018.

The homeless advocacy group also noted that the U.S. government does not conduct an official tally of the actual number of homeless deaths.

“Homeless death counts for each city or county are collected from a combination of local news reports, medical examiner office, and coroner findings, through a public records request, and direct correspondence with local organizers of Homeless Persons’ Memorial Day.

“News reports of death counts conducted by local community advocates, shelters, homeless service providers, and religious organizations are by far the most common group that contribute data to this count.”

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) stated that it doesn’t track official mortality rates among homeless veterans. However, the HUD 2023 Point-in-Time Count found that on a single night in January 2023, there were 35,574 homeless veterans in the United States.

“This reflects a 7.4 percent increase in the number of veterans experiencing homelessness from 2022,” VA press secretary Terence Hayes told The Epoch Times in an email.

“Looking deeper at the data, we see that of the veterans counted, 20,067 experienced sheltered homelessness, and 15,507 experienced unsheltered homelessness.

“Veterans who experience sheltered homelessness often live in places such as emergency shelters, transitional housing programs, or other supportive settings.

“In contrast, veterans who experience unsheltered homelessness live in places not meant for human habitation, such as cars, parks, sidewalks, abandoned buildings, and literally on the street.”

Despite these increases, he said, there is still an overall downward trend in veteran homelessness of 52 percent from 2010 to 2023.

“Within the last three years alone, there has been approximately a 4 percent overall reduction in veteran homelessness,” Hayes said.

He said that when a veteran without family ties or sufficient finances dies under the care of the Veterans Health Administration, the agency is responsible for ensuring burial in a national or state cemetery for veterans.

“No veteran should be homeless in the country they fought to defend,” Hayes said.

Origin of Potter’s Field

The term “potter’s field” comes from Matthew 27 in the Bible, according to the website of Old City Cemetery Museums and Arboretum in Lynchburg, Virginia.“After Judas betrayed Jesus for 30 pieces of silver and learned that Jesus had been condemned to death, his remorse led him to return the money to the high priests,” it reads.

“However, the priests could not return the money to the church coffers, because the law would not allow the church to benefit from blood money. Instead, they used the coins to purchase a field, called the potter’s field, for the purpose of burying the poor and unknown.

“Historians and scholars believe that the field was available for cheap because it had been used by a potter to harvest clay, and as such, was no longer valuable for farming or development.”

At Old City Cemetery, there are eight potter’s fields for the needy, dating from 1806 to the present day.

They serve as eternal homes for the homeless, the unidentified, criminals, and prostitutes—“anyone who could not pay for their end of life needs,” according to Whitney Wilder, administrative manager for the organization.

“Statistically, we see a lot of young people who die unexpectedly due to drug abuse or violence. We see a lot of older individuals [receiving financial support] from the state,” Wilder said.

The sad fact is that today, there hasn’t been much public interest in these obscure burial places despite efforts by Old City Cemetery to raise funding for their care and upkeep, she said.

However, Wilder said that some people recognize the importance of the services they provide and the necessity of maintaining them well.

Raising awareness, therefore, is critical to preserving potter’s fields to help people understand their role and the purpose their preservation continues to serve, she said.

“In four or five decades, we want descendants to be able to come to the grounds and pull a file on their ancestors buried in Potter’s Field, just like someone could come and pull a file on an ancestor buried in one of our other sections,” Wilder said.

“They are critical for genealogy and for future generations to be able to research their ancestry.”

In Arizona, every county tries to work within financial limits to ensure that every homeless person receives a dignified and cost-effective burial.

In 2021, the Arizona Department of Economic Security counted 821 homeless individuals in Pima County alone out of a total statewide homeless population of 5,460.

To Lie Down in Green Pastures

On July 12, the rough condition of Pima County Cemetery stood in sharp contrast to the lush green plots at Evergreen, basking in the shade of trees shielding row upon row of marble gravestones and acres of manicured lawn.However, the county cemetery lay parched and barren-looking in the late afternoon sun. At the entrance were two dried-out funeral wreaths crumbling at the foot of a triptych metal sculpture with an engraving that reads, “Gone But Not Forgotten.”

Inside the cemetery, some of the graves had rudimentary crosses and piles of stones around them. Other markers were basic headstones or granite slabs inscribed with the partial name of a deceased infant or simply “John Doe” to identify the person’s remains.

If there is a message, it is that there is a cost and a price for everything that persists even after death.

The Leal Funeral Home in Houston estimated that the average traditional funeral cost in Texas is between $6,700 and $16,700, including casket, service, burial, headstone, and extras.

According to Lincoln Heritage Life Insurance Company, a traditional funeral with cremation costs $6,000 to $7,000.

With financial assistance and volunteer labor factored in, the price of burials and maintenance in a county cemetery for the indigent is significantly lower.

Through her research, she discovered many errors and discrepancies in grave marker inscriptions at White Tanks, so she began creating her own virtual memorials on the website.

Over the past dozen years, Chesser has built 11 virtual cemeteries totaling 8,224 virtual memorials at a rate of 13 per week.

She has also taken hundreds of photographs of grave markers to accompany virtual monuments.

“I went back as far as I could to catch up with all the undocumented burials,” Chesser told The Epoch Times. “I just felt they need to be remembered. That’s why I started this.”

Her work has helped many people locate long-lost friends and relatives, earning her the online handle “Desert Angel.”

She recalled a woman from California who phoned her one day asking about her cousin, a homeless woman with a drug problem who was living on the streets of Phoenix.

After searching through her collection of online memorials, Chesser eventually found that the cousin had died.

“I truly believe that even though it’s a virtual memorial, people should be with the people they loved and who loved them,” she said.

With the summer heat wave, she foresees that more homeless people will die from exposure on the streets—more unshed tears for the county’s unknown poor and downtrodden.

“It’s heartbreaking,” Chesser said, “because they were sons and daughters. They could have been mothers and fathers—cousins. They were school chums. They were children at one point. They laughed, and they cried, and they hurt.

“I just wanted to be able to say: ‘You know what? You counted in the world.’”