This Italian ocean liner was named after an admiral from Genoa. In 1953, it was hailed as the largest, fastest, and safest at the time. It had a gross tonnage of 29,100 and could hold 1,200 passengers and crew members.

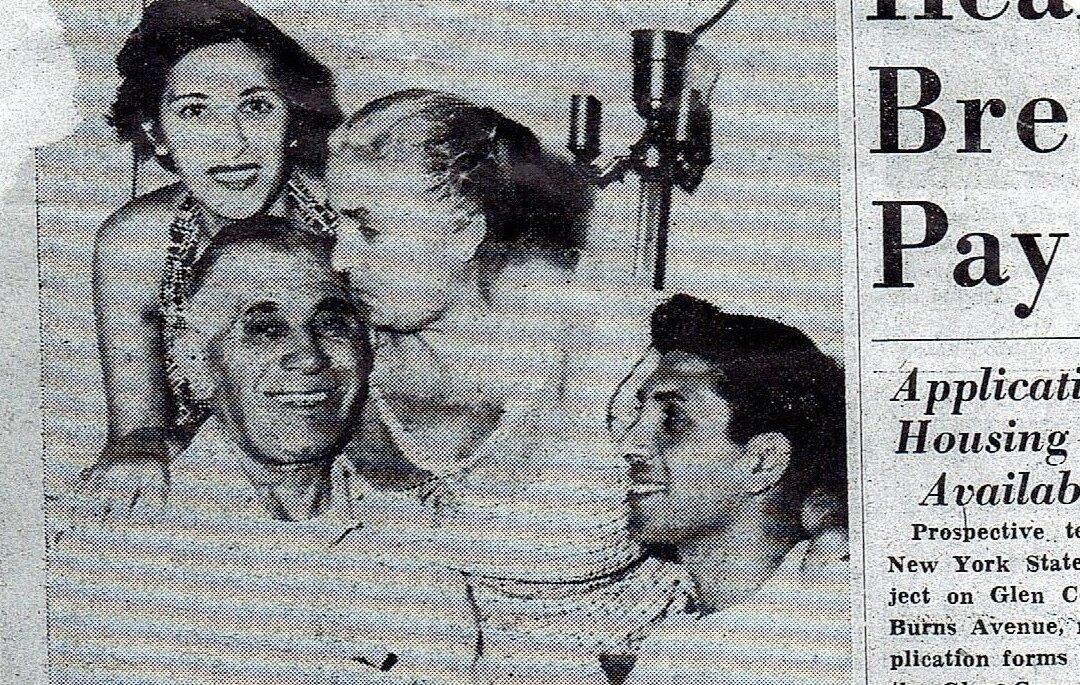

In 1956, my family and I were on the ship to see my grandfather off. My eight-year-old eyes had never seen anything like it before. I gazed out at a huge dining room with a deep red patterned carpet and hundreds of gilded ornate chairs and tables set for meals. So much gold on the ceiling! I was impressed as I scanned back and forth to take in the sight. When the refreshments were over, he was out on the deck and we were waving our smiling good-byes from the pier.