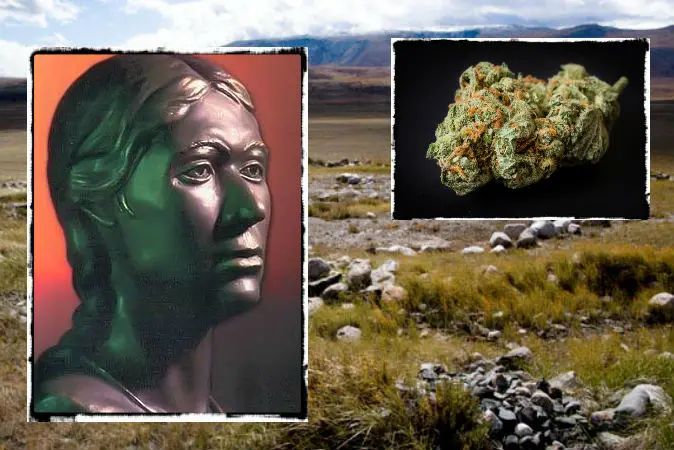

From The Siberian Times: Preserved by ice, the ancient woman, who died at the age of 25 and is covered in tattoos, used cannabis to cope with her ravaging illness.

Studies of the mummified Ukok “princess”—named after the permafrost plateau in the Altai Mountains where her remains were found—have already brought extraordinary advances in our understanding of the rich and ingenious Pazyryk culture.

The tattoos on her skin are works of great skill and artistry, while her fashion and beauty secrets—from items found in her burial chamber, which even included a cosmetics bag—allow her impressive looks to be recreated more than two millennia after her death.

A model of how the Ukok princess may have looked in life. Wikimedia Commons