On Monday evening in China, the Supreme People’s Court and Supreme People’s Procuratorate flooded the Internet with news of a new regulation: anyone who writes a microblog post that contains “slander,” and which goes viral, could be imprisoned for three years. The threat of jail time is the latest measure in a campaign some are comparing to the Cultural Revolution.

The court and prosecutor’s office in China are both controlled by the Chinese Communist Party, so the Party almost certainly vetted the rule, which was described as a “judicial interpretation.”

It said that authors of “slanderous” posts that receive a viewership of over 5,000, or are forwarded more than 500 times, are liable for punishment.

The worse the slander, the worse the punishment, authorities said. And they made clear that they’re the ones who define slander. In the most serious cases, jail sentences will be given out.

This regulation is the latest and most frontal assault in a “strike hard” campaign the Party has waged for the last several months against online opinion.

“The Propaganda Department always used to control public opinion. Now with the rise of microblogs, it has grown out of their control. They want to take back the power,” said Zan Aizong, a freelance writer and active blogger and microblog user in China, in a telephone interview.

Microblogs, called Weibo in Chinese, have been around since 2009. The most popular is Sina Weibo, which was modeled closely off Twitter, a service that is blocked in China. The platforms allow users to send messages of 140 characters or less which can be viewed and shared by millions of people in a matter of minutes, making it potent tool for intellectuals and activists.

No phenomenon better exemplifies the ability of Weibo to influence the views of the public than the rise of so-called “Big Vs,” accounts run by people who have been verified by Sina. They often command millions or tens of millions of followers, and a single message they publish can spread across the Internet rapidly.

“The influence of Weibo is so big, bigger than the propaganda authorities,” said Zan Aizong. “To shut them down, they’re taking their sword to the Big Vs.”

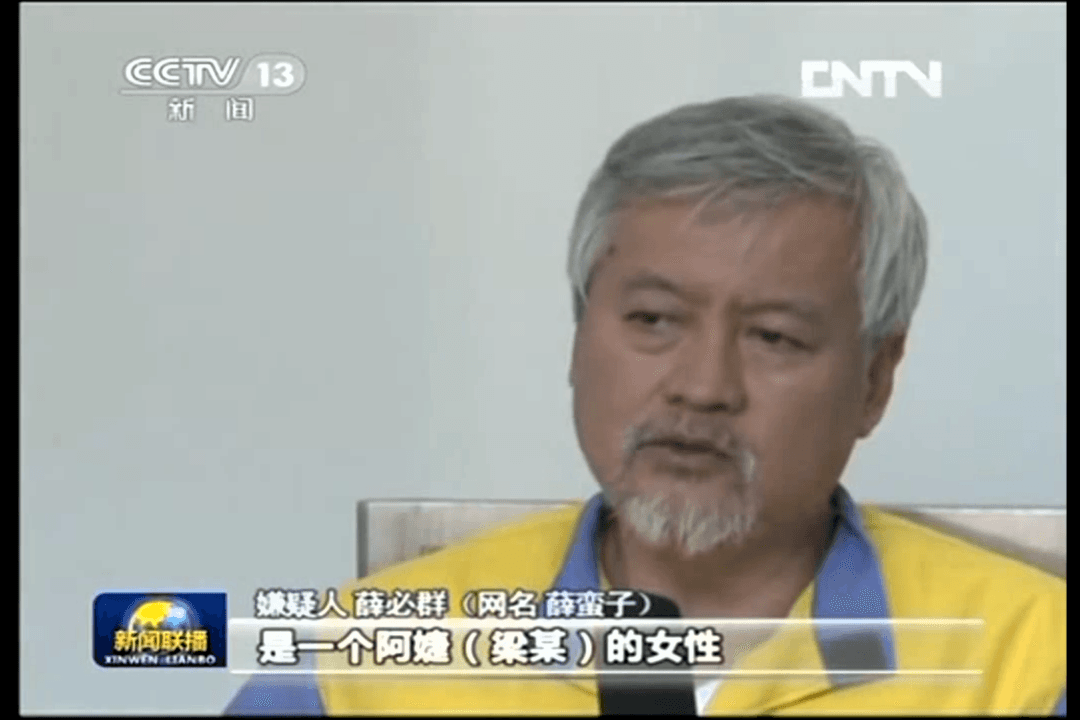

The most high-profile target so far has been a millionaire venture capitalist and naturalized American citizen, Charles Xue, 60, based in Beijing. His Weibo account was often host to pro-constitutionalist views, and occasional criticism of the Chinese regime.

In an episode of public self-criticisms redolent of the Cultural Revolution, he was brought onto China Central Television, the state broadcaster, and made to “confess” to having visited prostitutes and organized “sex parties.” In a yellow and blue prison uniform he said, “When I was working abroad I came across prostitution in countries such as Thailand and the Netherlands.” His eyes were fixed to the left, as though he were reading the confession. “He became obsessed with the disgusting habit of visiting prostitutes,” the news announcer explained.

On the Chinese Internet, many commentators thought the exercise in humiliation was a warning shot to other Big Vs, as the regime lays down the law on permissible discourse in the online realm. People’s Daily, the Communist Party’s mouthpiece, ran a headline saying, “The ‘Big V’ Tag Will Not Shield You From the Law.”

Many thought the Party had itself disregarded the law with the public shaming of Charles Xue. Wang Ganlin, head of the in-depth reporting unit at Guangzhou’s Yangcheng Evening News, pointed out that just a month prior five judges in Shanghai had been caught visiting prostitutes. The Party’s clamped down on the news and punished the officials quietly. No judge was made to confess on television. “I think what they did to Charles Xue was revenge,” Wang said in a telephone interview.

The shaming of public intellectuals and threats of jail against common Internet folk are two of the most recent measures the Party has taken in its broader campaign. It wishes to stamp out the calls for political change from increasingly informed and discontent population.

“I feel that the way they’re cracking down on online rumors is a political movement, a little like the Cultural Revolution,” Wang Ganlin said.

The crackdown comes along with a range of other ideologically heavy talk by the new leadership of the Chinese Communist Party.

At a Party conference in late August Xi Jinping, the head of the Party, said that “Ideology and propaganda work must be at the center” and one of the “basic duties” of Party members. Ideology and propaganda work, he said, were to “consolidate the leading position of Marxism in the ideological sphere,” and “unite the Party and people in struggle.” Party members had to firmly believe in Marxism and communism, he said.

Similarly, Beijing Daily, a state-run newspaper, recently ran an editorial titled “Do Not Leave Space for Universal Values.” It said, “The Internet has become the main battlefield for ideological struggle. The Western anti-China forces seek to advance this ‘biggest variable’ to ‘topple China,’” according to a translation by Chinascope, which analyzes Chinese media.

“Whether we can hold up and win in the battlefield directly relates to the security of our ideology and the ruling Party’s power. It is a matter of life and death. Dare to fight and dare to show the sword. That is the choice we must make now!”

Earlier this top Party leader held meetings for the cadre corps warning them against the “Seven Don’t Speaks,” according to a number of accounts. The seven forbidden items include talk of civil rights, freedom of speech, civil society, and universal values—the same ideological menu that is being targeted in the Internet crackdown.

Whether it will have the desired effect is unclear. Xu Xiang, a writer and a member of the Independent Chinese PEN Center, said that the Internet had been an outlet for social discontent. Many people in China are increasingly frustrated with the corruption, privileges enjoyed by Party officials, abuses of power, and social injustice. Closing off that outlet won’t help matters, he said. “Television is controlled. Newspapers are controlled. The only channel, Weibo, is now being shut off. It’s going to turn the whole society into a powder keg.”

Lu Chen contributed reporting.