The Flemish historian and writer David Van Reybrouck has recently triggered a minor sensation in the Low Countries by insisting that Western democracies are suffering so much election fatigue (electoral democracy is “killing” democracy, he says) that what is now needed is the replacement of periodic elections, the ritual of citizens choosing parliamentary representatives, by government based on random selection and allotted assemblies of citizens considered as equals.

Van Reybrouck knows how to turn a political phrase. “The realities of our democracies disillusion people at an alarming rate,” he says. “We must ensure that democracy does not wear itself out.” He’s convinced that elections are paralyzing democracy because electoral democracy is a contradiction in terms, and in practice.

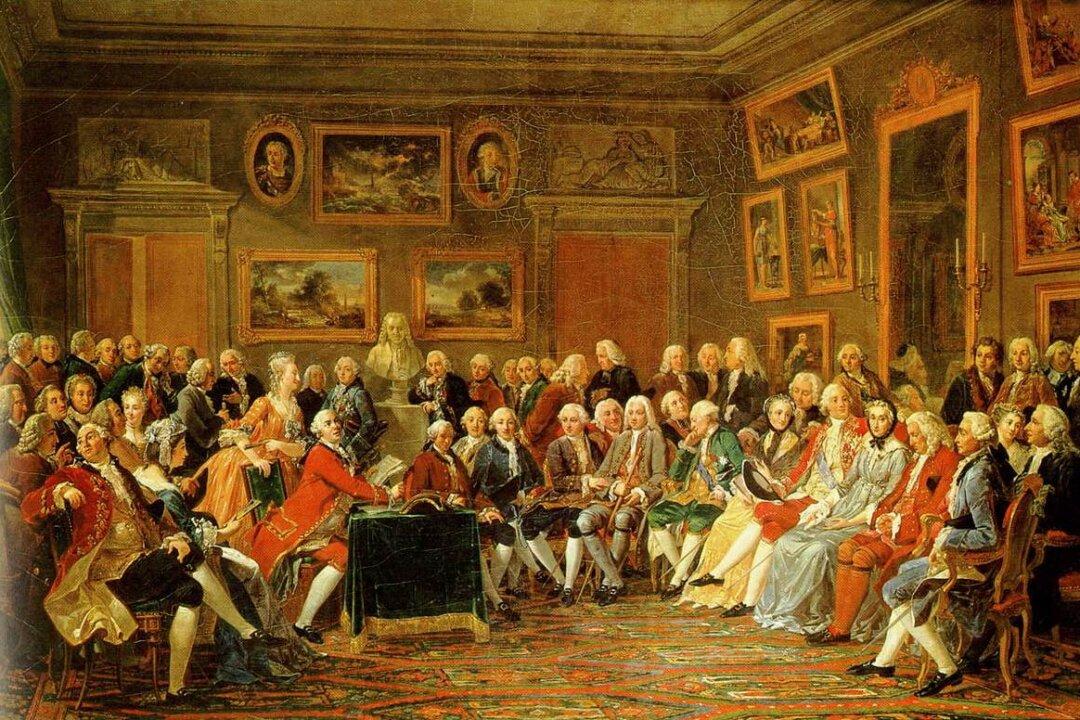

Representation is essentially an aristocratic device: a form of delegation according to which “the person who casts his or her vote, casts it away.” From his neo-classical perspective, elections “are not only outdated as a democratic procedure, they were never meant to be democratic in the first place. Elections were invented to stop the danger of democracy.”