Jiang Zemin’s days are numbered. It is only a question of when, not if, the former head of the Chinese Communist Party will be arrested. Jiang officially ran the Chinese regime for more than a decade, and for another decade he was the puppet master behind the scenes who often controlled events. During those decades Jiang did incalculable damage to China. At this moment when Jiang’s era is about to end, Epoch Times here republishes in serial form “Anything for Power: The Real Story of Jiang Zemin,” first published in English in 2011. The reader can come to understand better the career of this pivotal figure in today’s China.

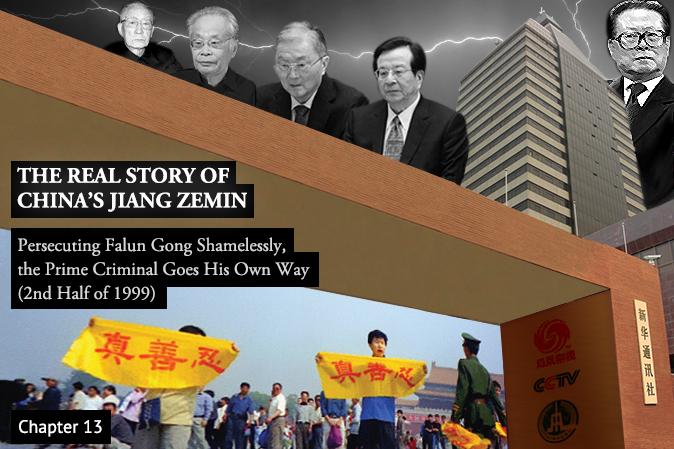

Chapter 13: Persecuting Falun Gong Shamelessly, the Prime Criminal Goes His Own Way (2nd Half of 1999)

A number of major events transpired during the 15 years of Jiang Zemin’s rule (including the past two years, post-retirement, in which he controlled state affairs from behind the scenes), among which are counted the return of Hong Kong and Macau to China, China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO), and the suppression of Falun Gong. Of the events, only the suppression of Falun Gong was spurred forward by Jiang, while the others happened either due to luck or as a result of other people’s hard work.When Jiang banned Falun Gong it was the beginning of his political downfall. One might say that after Jiang became one of Beijing’s power elite on the heels of the Tiananmen Massacre, he methodically consolidated his power through a series of brutal political struggles. But the suppression of Falun Gong quickly became an albatross for Jiang. Jiang didn’t expect this in the least, anticipating instead that Falun Gong could be swiftly crushed. Jiang’s political fate was tied to the campaign against Falun Gong from the moment he went his own way in launching it. All of his decisions came to revolve around the issue.