Jiang Zemin’s days are numbered. It is only a question of when, not if, the former head of the Chinese Communist Party will be arrested. Jiang officially ran the Chinese regime for more than a decade, and for another decade he was the puppet master behind the scenes who often controlled events. During those decades Jiang did incalculable damage to China. At this moment when Jiang’s era is about to end, Epoch Times here republishes in serial form “Anything for Power: The Real Story of Jiang Zemin,” first published in English in 2011. The reader can come to understand better the career of this pivotal figure in today’s China.

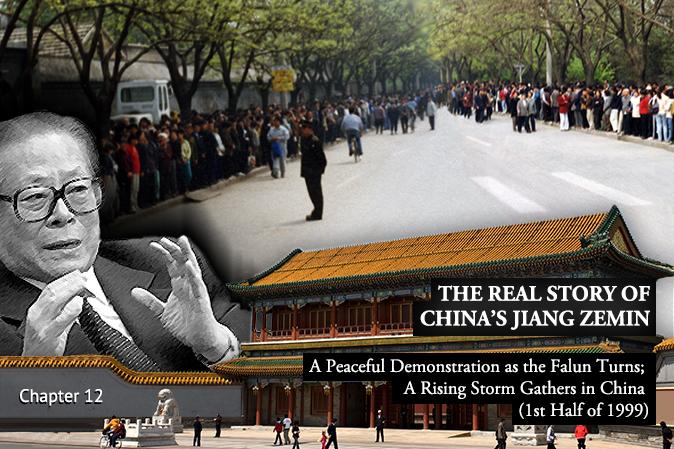

Chapter 12: A Peaceful Demonstration as the Falun Turns; a Rising Storm Gathers in China (1st Half of 1999)

The year 1999 proved to be a troubled one for China.The Balkan Peninsula had always been regarded as a “powder keg,” and it was in 1999 that a fateful spark was finally ignited. The Serbian army that year slaughtered thousands of Albanian civilians in a wave of ethnic cleansing, forcing more than 1.5 million Albanians to flee their homeland. As described by the refugees, massacres took place in at least 75 cities and villages in Kosovo. More than 5,000 ethnic Albanians were eliminated in mass executions.