News Analysis

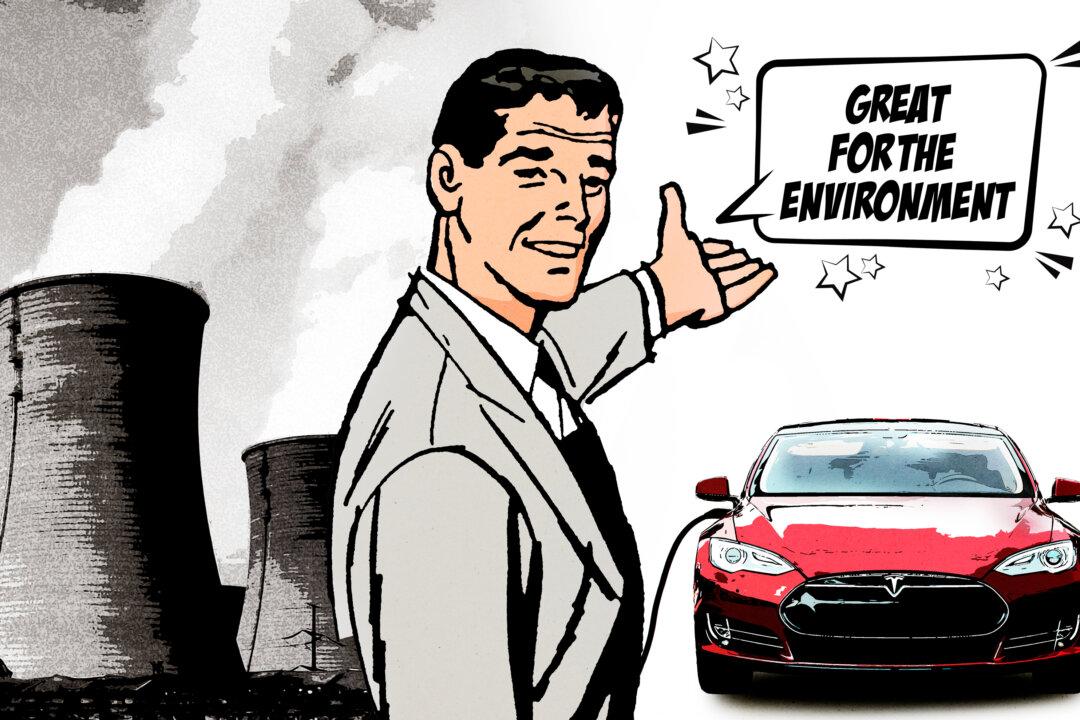

The Biden administration can’t force you to buy an electric car, although by capping tailpipe emissions and other coercive measures, it can compel producers to severely curtail the manufacturing of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles and drive up the cost of gasoline-powered cars.