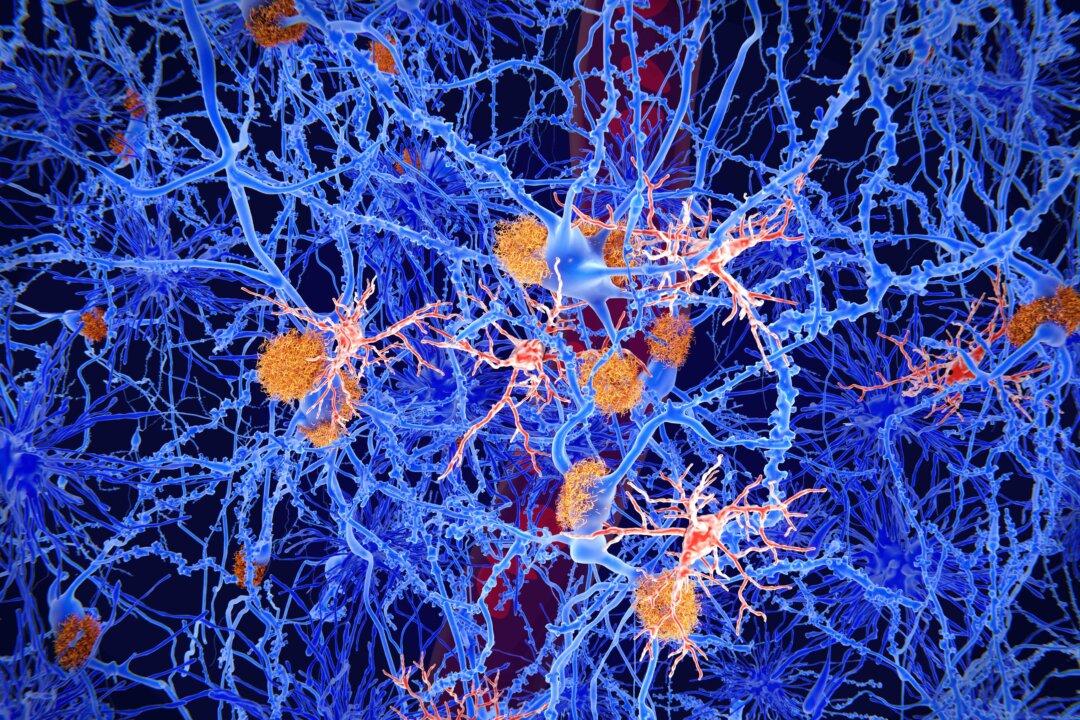

A good night’s sleep has always been linked to better mood, and better health. Now, scientists have even more evidence of just how much sleep – and more specifically our circadian rhythm, which regulates our sleep cycle – is linked to certain diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease. A team of researchers from the United States have found further evidence that the cells which help keep the brain healthy and prevent Alzheimer’s disease also follow a circadian rhythm.

Our circadian rhythm is a natural, internal process that follows a 24-hour cycle. It controls everything from sleep, digestion, appetite and even immunity. Things like outside light, when we eat our meals and physical activity all work to keep our circadian rhythm in sync. But even small things like staying up a bit later than normal, or even eating at a different time than we’re used to can knock this internal “clock” out of whack.