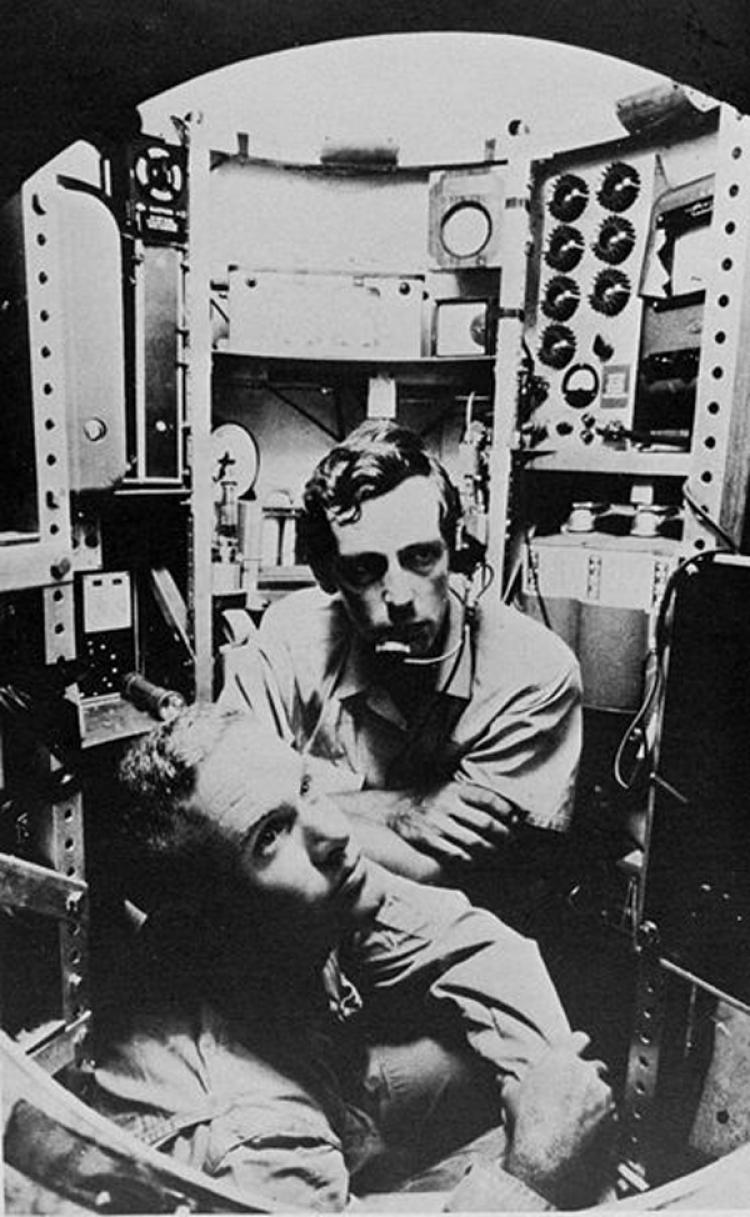

Spotlights peered into endless darkness as the vessel descended into the abyss. In the hollows of a small orb hanging below the blimp-like bathyscaphe Trieste submarine, two scientists shivered through the unrelenting cold of the ocean’s depths.

The journey would take them to the deepest known part of the ocean, the Challenger Deep at the southern end of the Marianas Trench. At nearly 36,000 feet, Jacques Piccard and Lieutenant Don Walsh would pilot the first vessel to reach this depth—a place where unknown creatures dwell and where the crushing pressure of the ocean reaches 16,000 pounds per square inch.

More than 50 years later, two groups are gearing up to make the descent once again.

Although the first and only manned mission to the bottom of the Challenger Deep on Jan. 23, 1960, was a success, the mission was limited by the technology of the time.

It made a vertical dive, stayed at the ocean floor for 20 minutes, and then began its ascent. Exploration was constrained by the location of their arrival, however, and their only window to the murky depths was a tiny porthole that had cracked on the way down—a factor that caused Piccard and Walsh to cut the journey short.

Five decades of technical advances ensure that the next submarine to make the dive “is much more capable of exploring” and “will make significant transects at the bottom of the trench, and enable significant filming,” said Adam Wright, principal mechanical engineer for Hawkes Ocean Technologies, in a phone interview.

The California-based company focuses on making both manned and unmanned submersibles, yet takes a different approach to the concept. Wright refers to their subs as “positively buoyant flying machines,” as opposed to the typical hot air balloon models.

When their “DeepFlight Challenger” submarine makes the dive as early as this summer, it will cruise along the bottom of the Challenger Deep, bringing more detail and exploring more areas than anyone could have fathomed in 1960.

Hawkes makes the sports cars of submarines. The sleek, winged vessels with large windows function the same as a jet, only reversed. While jets use motion to create lift, Hawkes subs use motion to descend. Since the vessels are positively buoyant, however, if they stop moving, they start to ascend.[youtube]_Sk_XEHfqwk[/youtube]

A Dream Realized

Although two unmanned missions were launched in 1996 and 2009 using remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), the mysteries of the Challenger Deep are about to get an unprecedented level of exposure as some of the highest profile adventures in the world line up.