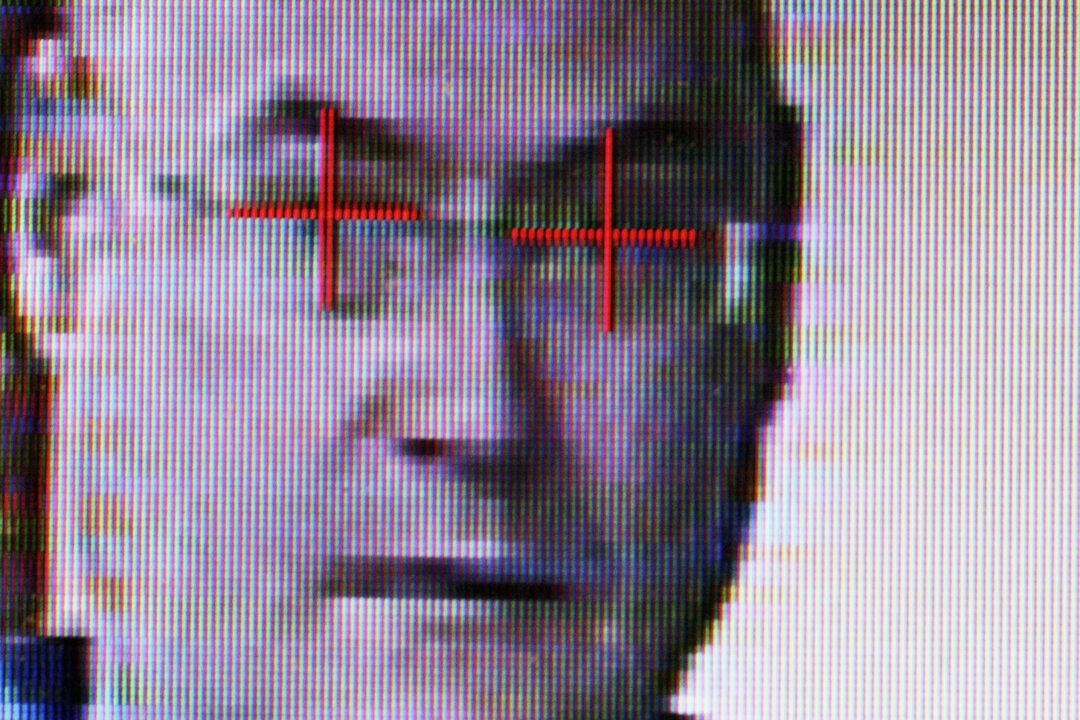

South Australia (SA) police will not be granted access to facial recognition services embedded in a new $3 million surveillance system due to concerns about indiscriminate use and lack of regulation.

The federally-funded system—which also features object and license plate recognition—will cover the City of Adelaide following the retirement of existing ageing infrastructure. The rollout is expected to conclude within the next 18 months.