As a police officer sits in the hallway outside her home, watching her day and night, would-be prospective candidate Wang Xiuzhen was compelled to halt her campaign activities.

It was her third time seeking election as a deputy in her home district of Chaoyang in the past decade. Once again, her hope has faded.

Wang is just one of 14 grassroots citizens in Beijing who now have to give up their bid to run in district elections—the only opportunity every five years for citizens to cast their votes in the communist-ruled country—out of concern for their own safety.

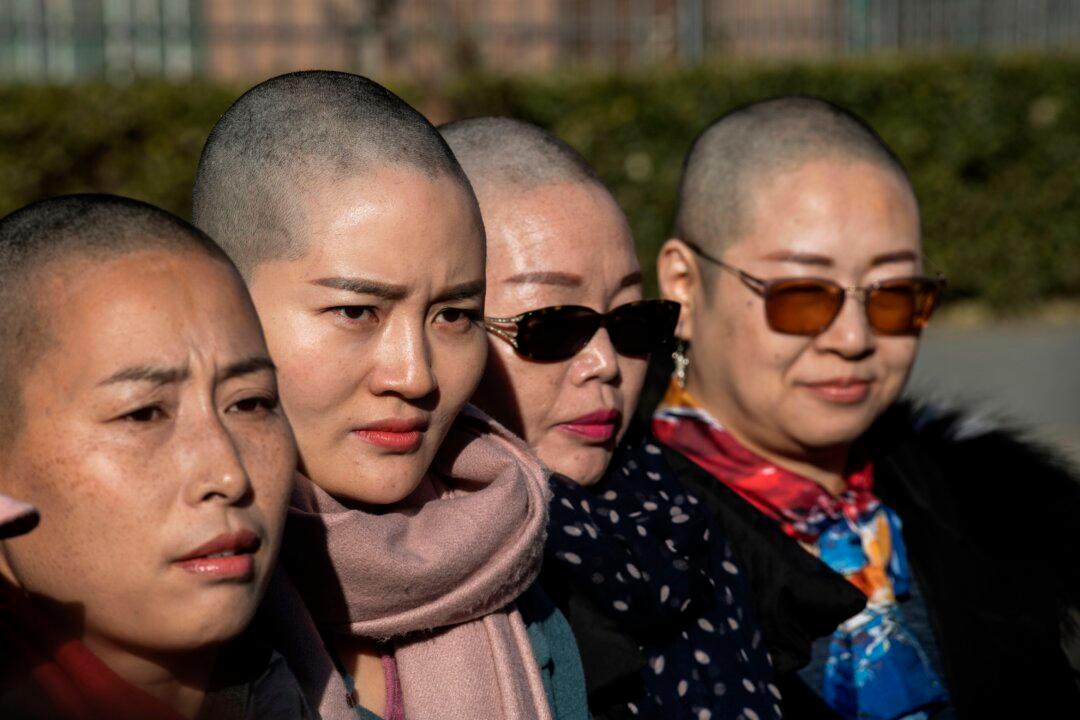

Many of the 14 are Chinese wives supporting their imprisoned husbands who are prominent human rights lawyers, including Li Wenzu, Wang Qiaoling, and Liu Ermin.

Yet, their passion and hope to channel this frustration for the greater public good was not welcomed by the ruling Party.

During the two-week period of campaigning, at least 10 of the 14 independent candidates were watched, guarded, or threatened by police or the rural government. Some were banned from leaving home, even to walk a dog.

“Your case has been determined. This time, it’s dangerous [for you],” another said.

Wang is the wife of jailed rights lawyer Li Heping, one of the hundreds of rights lawyers and activists who were arrested by the Chinese regime in a nationwide manhunt on July 9, 2015, a day that’s often referred to as the 709 Incident.

The mounting political pressure held the 14 back.

“Under such fear and pressure, and for the sake of the personal freedom and lives of the 14 of us, we declare a halt to the candidacy of independent candidates,” the Monday statement reads.

Another two candidates Li Hairong and Guo Qizeng said on Oct. 27 through Chinese social media WeChat that the local township government had launched a house demolition campaign against villagers since the two announced their candidacy.

The twice-a-decade Beijing Municipal rubber-stamp legislature elections will be held on Nov. 5 to nominate nearly 5,000 district representatives and more than 10,000 township representatives.

Netizens said on Twitter that “You have proved through your own experience that the so-called ‘whole-process democracy’ they have just claimed is trash.”

Chinese-Style ‘Democracy’

Two days before the 14 publicized their candidacy, Chinese leader Xi Jinping described China’s political system as a “whole-process” democracy, as he addressed an Oct. 13 meeting of the rubber-stamp legislature work conference in Beijing. Yet, the regime has long kept a tight grip over the election procedures.In China, representatives at all levels up to the rubber-stamp legislature are usually officially appointed, excluding those for urban districts and rural counties, which goes through “universal suffrage.”

Despite this provision, independent candidates who attempt to get their names on the ballot face a difficult challenge including harassment and detention by the police, on top of procedural roadblocks.

Among the 14 activists, Ye Jinghuan is also running in the election for the third time, despite receiving police threats in the past.

After she announced her first candidacy in 2011, she was quickly targeted and was beaten by uniformed police. The second time, in 2016, local neighborhood committee members and plain-clothes police tried to block her from campaigning.

“They surrounded our house, surrounded our courtyard so as to stop us from going to populous places to campaign for votes,” she told The Epoch Times in a previous interview, adding that the police also tried to prevent Western media reporters from interviewing her.

Ye decided to petition for candidacy after she and her sister became victims of a futures investment scam in 1998, where hundreds lost their life savings.

“We wanted to explain our situation to the [rubber-stamp legislature] representatives because they have some power, they can at least talk to government authorities,” she said.

Moreover, the vast majority of China’s grassroots population has no chance to see the ballot. Those who are eventually elected, seemingly fail to fulfill the duties, according to rights activists.

“We have often looked for [rubber-stamp legislature] representatives through all different channels, hoping they could help us to convey our concerns to the government, but we have no hopes of meeting with them,” the 14 said in a previous declaration.