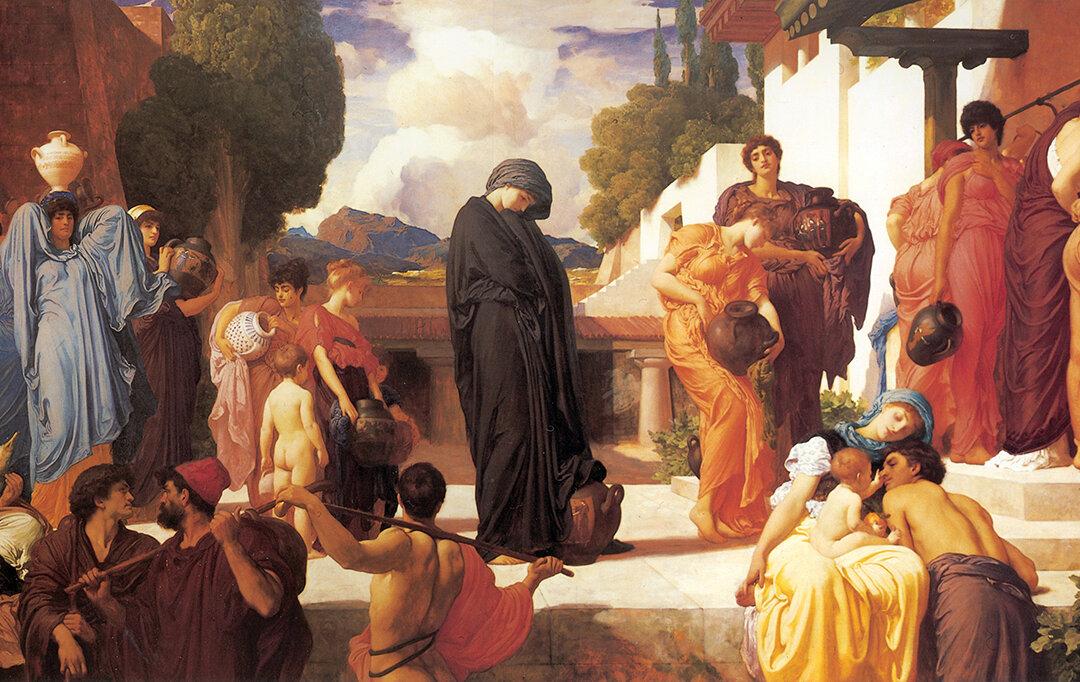

“Captive Andromache” (circa 1888), conceived of and created by academic painter Frederic Leighton (1830–1896), engages with the relationships between mother and child and husband and wife. These loving relationships, rendered with Leighton’s sensitive brush, provide a restorative antidote to the familial and national splintering that Andromache felt in the wake of the Trojan War. The painting reminds us that we often learn what we have through loss.

Leighton’s Realization of the ‘Iliad’

Some standing by, Marking thy tears fall, shall say ‘This is she, The wife of that same Hector that fought best Of all the Trojans when all fought for Troy.’

The scene that “Captive Andromache” portrays is not a depiction of an event in the epic poem. It’s actually an imagined reality articulated by Hector in Book VI of the “Iliad,” in which the Trojan hero envisions the enslavement of his wife by the Greeks upon his death. Thus, in meditating on Hector’s death on the battlefield and following the direction of Andromache’s gaze in the painting, the scene of the widow’s lament in Book XXII of the “Iliad” is called to mind.In her lament, Andromache expresses sorrow at the fact that her son, Astyanax, will be raised without a father, reflecting on the lack of emotional security he will feel in the world as a result of Hector’s death. Hector is not only Astyanax’s father and Andromache’s husband. Within the architecture of the “Iliad,” Hector symbolizes a sort of paternal ideal; his character embodies a vision of order and peace.

Composing a Narrative

It is early morning in the painting. The townsfolk gather at the communal fountain to fill their water jugs, their jewel-toned robes aglow in the morning light. Aurally evoked is a pleasant babble of voices mingled with running water, a white noise soundscape against which the central, internal drama unfolds.

Even without knowledge of the story the painting is telling, the viewer’s gaze is directed toward the psychological complexity embodied in Andromache, arrayed in black drapery with her face downcast in profile.

While the normal world bustles on around her, she is separated from its rhythms as the world-shattering knowledge of the tragedy settles in, establishing psychological distance between herself and her surroundings.

There is a striking resemblance between the saffron-robed woman and Andromache. Of all the figures in the painting, these are the only two with the same gesture and angle of the neck in profile, with the same shapes abstracted as shadows.

In contrast to their facial similarities, the saffron-robed woman strikes a much more dynamic gesture than Andromache’s withdrawn stance, as if Leighton is suggesting that she represents a version of what Andromache could have been if she had not lost her husband. The sheer chroma of the woman’s robe, evocative of the rich warmth of a fire or a flower petal penetrated with sunlight, is in stark contrast with the obsidian robe that Andromache dons to indicate mourning.

In fact, the figure with whom Andromache shares the most sartorial resemblance is that of the old woman weaving at the left bottom corner of the composition. The spinning woman, whose face is also portrayed in profile (although it is entirely in shadow) is one of two figures (aside from Andromache) who wears black, as if to suggest that the weaving woman’s present is Andromache’s near future, and that age and loneliness will soon catch up to the widow.

A Family Triad

If we were to follow Andromache’s mournful gaze, our eyes would land upon the family triad at the painting’s bottom right. The mother, who occupies the apex of a pyramidal composition (meant to evoke Madonna and Child representations of the maternal ideal), is the other black-clad figure, aside from the woman spinning and Andromache herself. Again, Leighton is suggesting that this woman is a version of Andromache who could have been if Hector had not died.

Her infant child is perched contentedly upon her lap and she is completely engrossed in her baby’s face, watching as he grasps his father’s nose. There is a lovely knowing exchange taking place between father and child as they gaze into each other’s eyes, just as there is a shared connection happening among all members of the family triad.

Leighton, who became president of the Royal Academy of Arts (London’s premiere art institution) in 1878, was known for paintings that embodied the moralizing, allegorical, and Hellenizing spirit of Neoclassicism and the “art for art’s sake” argument of Aestheticism. “Captive Andromache,” which is in direct conversation with Homer’s epic, is one of his more neoclassical paintings.

While upholding the methods of academic art to orient viewers toward the transcendence of Platonic forms, Leighton ventures beyond pure beauty, portraying the pathos of Andromache’s predicament. In this way, like Homer, Leighton humanizes the Trojans, conveying the fragmenting effects of war for everyone involved. As we follow Andromache’s gaze, we are invited to reflect upon the restorative potential of our most important relationships, that of husband and wife and mother and child.