Commentary

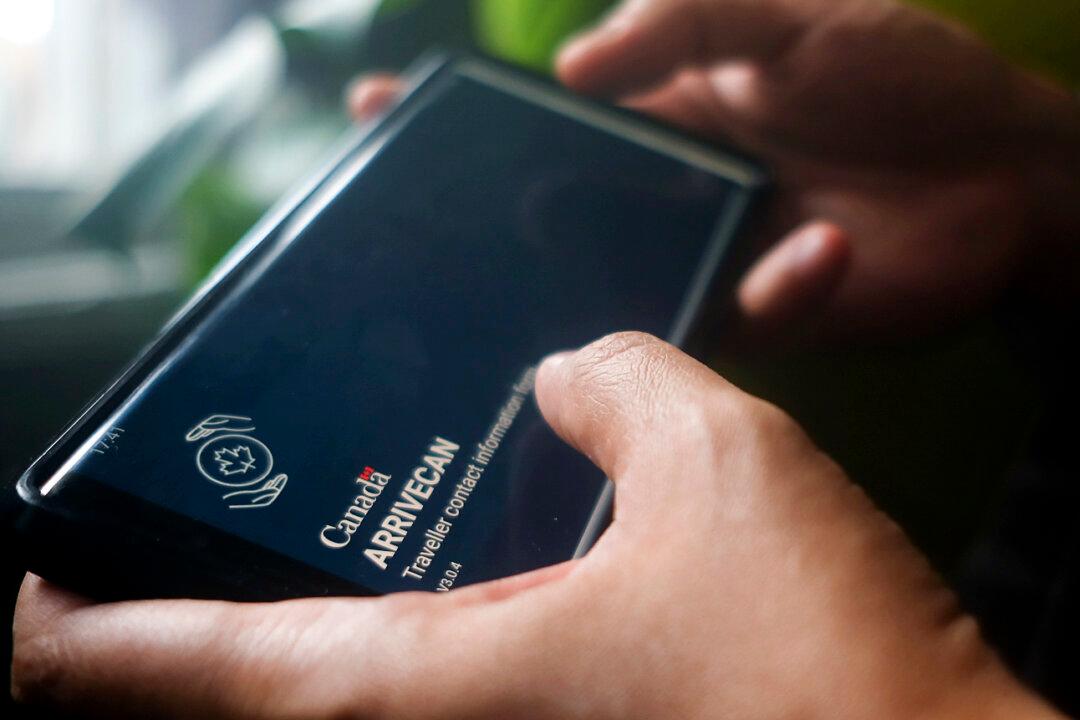

Anyone who had any experience of ArriveCan knew what a disaster it was: In the interests of declared efficiency it harassed and beleaguered practically everyone who entered the country.

Anyone who had any experience of ArriveCan knew what a disaster it was: In the interests of declared efficiency it harassed and beleaguered practically everyone who entered the country.