“I call it industrial art,” Claus Fuchs said. Collecting and restoring nautical antiques is his passion, that and riding his motorcycle. For this one time Washington, DC based Chief of Engineering for Comsat, old brass, bronze and copper from ships, that have seen service on the high seas and once voyaged around the world, is as alluring as sculpture and art. Among fine porcelains, cut crystal and antiques is a collection of ship’s hardware: large brass binnacles, engine telegraphs, steering columns, fog horns and running lights.

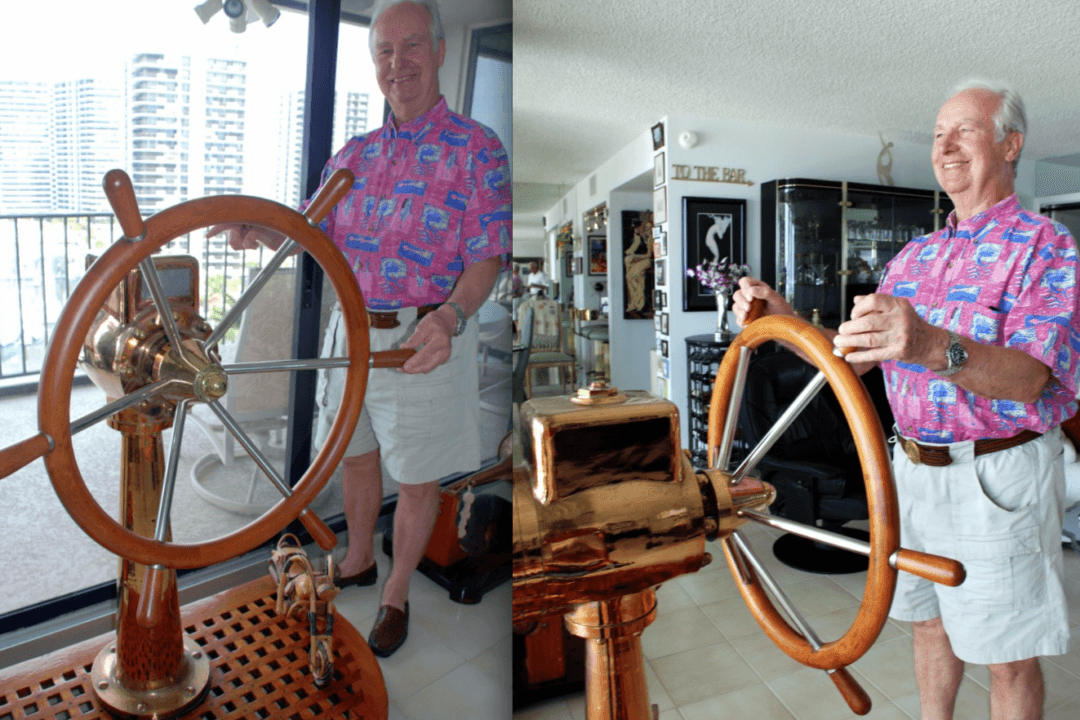

He lives on the top floor of a condo overlooking the Atlantic Ocean. The building is named South Quay in Old Port Cove. An open-air balcony and floor to ceiling sliding glass doors offer breathtaking views of marinas and blue water. Claus can stand in front of his living room window, take hold of the ship’s wheel and set a course anywhere his imagination takes him. It is an unusual hobby but one that enables him to discover nautical treasures in junkyards and antique shops then turn them into working, polished gems to decorate his home.

“This was made in Denmark. All the nuts and bolts are made on the English system. The ship had to be made for British off shore oil and gas support. It weighs 350 pounds. It’s a hydraulic thing. The pump inside is stainless steel and bronze. I took it apart and polished it inside and out.” Claus is meticulous. When he says polished, everything shines. The large ship’s steering column and wheel are based on a wood platform. That too shines as do all of the antique teak bases he uses to display and support his collection.

“Most of this comes from Culpepper’s Nautical Décor in West Palm Beach. I go down there and spend hours. This compass is early 40s. Somebody took it off a British ship and mounted it on this platform,” Claus said. He went to a ship’s compass that had somewhere and somehow been adapted for use on another vessel, probably based in India.

“This is primitive welding. I think India or Bangladesh. It has been mounted on a copper steam pipe. There are no compensation balls so I assume it was used on a wooden ship where there would be no metal interference with the compass. Otherwise they would have to set the iron compensation balls to make adjustments. It is a good compass that has been given third world application. The wooden base is teak. I worked on it three weeks. It had been hollystoned so much when it was part of a ship’s deck that there was hardly anything left of the screws.” His work is precise and admirable.

“Every ship gets a maker’s plate. They are cast in bronze usually. The plate tells where the ship was built, what year and has a number. This one is from Norway.” Claus has fashioned end tables from bronze and brass maker’s plates. Glass tops show off the design and make the table useful for glasses or cups. In most cases maritime records reveal the history of the vessel. Claus has corresponded with shipyards to obtain pictures and information about the ship that once bore the maker’s plates. Many met their fate in breaker’s yards in India, Bangladesh, Philippines and China.

One compass and binnacle Claus is restoring, lovingly polishing it with Wendl brass and bronze polish imported from Germany by Reckitt Benckisser, shines in his workshop. “You can see why my wife Elizabeth no longer has her walk-in closets,” he laughed. Two large walk-in closets in what would have been a den have been turned into storage for his tools. The den is now an office-workshop. “You can’t polish brass on a white carpet. I put towels down.”

The tell-tale compass has two sides. One that could be seen on the bridge where it was installed at the steering pedestal the other side seen below deck in the captain’s cabin. A series of lenses magnified the underside compass so that the captain, lying in his bunk in his cabin directly below the bridge, had only to look up to check his vessel’s course.

“I never saw anything like it. The compass was made by Weems in Bremerhaven, Germany. The brass binnacle was made by Navis-Plath in Bordeaux, France. A combination French-German firm.

Nearby were ship’s bridge and engine order telegraphs. Each was carefully restored. Each piece in perfect working order, ship shape, as when used on a World War II era Liberty Ship, long ago sent to a breaker’s yard for scrap. There are Liberty Ship hatch covers in pine and teak wood, bronze wrenches from mine sweepers, a bronze air horn from a German tug boat marked Zollner, Kiel. It is called a ‘Makrofon.’

“These apartment doors are bland. I used flooring. This latch is from Culpepper’s. The wind blows the door shut so I have this ship’s latch to keep it open. This old auto horn is what my guests use. They reach in like so, toot the horn, open the latch and come in.”

“I do this for fun. I have many hobbies. I wonder how I could ever have held down a full-time job,” this affable collector of nautical decorative items laughed. Visiting his home is like taking an ocean voyage long ago.

“Today’s ships have nothing made of wood, bronze or brass. They are steered with little levers on the bridge. Push buttons,” David Culpepper said from his warehouse where everywhere there is a jumble of raw material for decorators with a nautical bent.