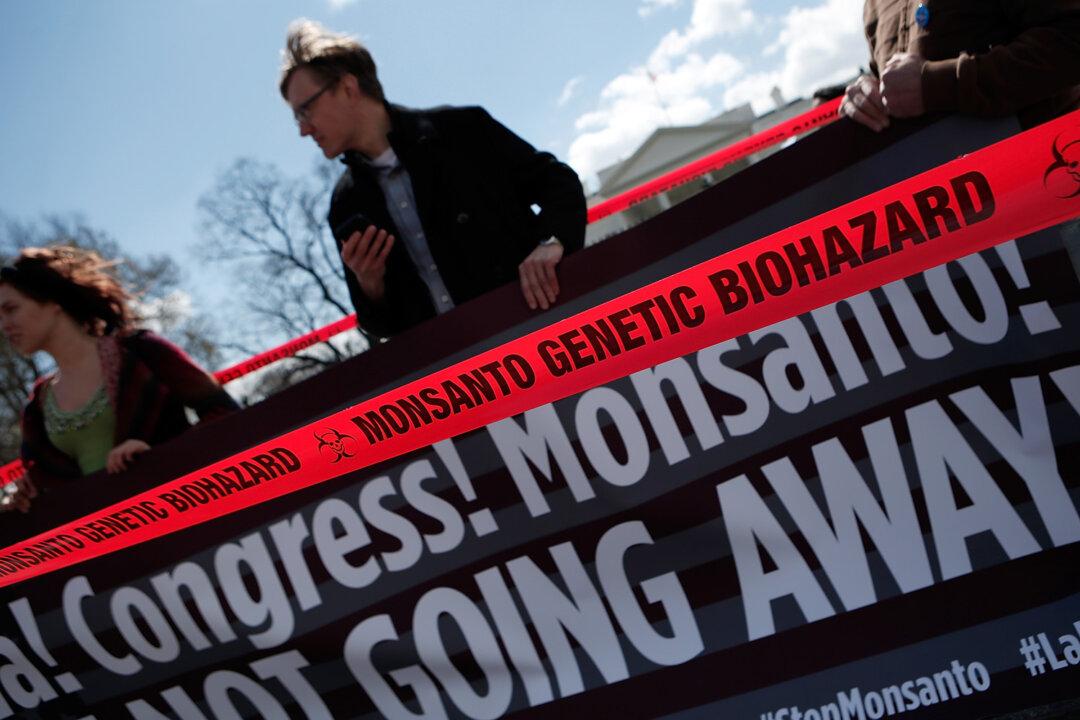

The White House passed a temporary budget bill nearly three weeks ago, but a small provision buried deep within the legislation continues to draw scorn and protest. Supporters of the measure say it’s much ado about nothing.

The provision’s official title—Section 735 of Senate appropriations bill HR933—doesn’t say much. The debate is revealed in the nicknames.

Supporters call it the Farmer Assurance Provision, and portray the rider as a minor regulatory adjustment necessary for farmer protection. Critics call it the Monsanto Protection Act. For them, the measure is a blatant attack on both farmers and democracy to protect biotech industry profits.

An aura of secrecy and deception surrounding Section 735 have raised as much concern as the changes to policy. The earmark was submitted anonymously into an urgent six-month budgetary measure designed to keep vital government functions afloat. Critics say it was not given the legislative attention it deserved.

“We’re certainly outraged because of the impact that it would have on many farms, but we were just as outraged at the lack of transparency that it had,” said Dave Murphy, founder of the farming advocacy nonprofit Food Democracy Now (FDN), in a phone interview.

“Legislation should not be done under cover of darkness in backroom deals, and if there’s a provision that has this type of impact on farmers and the environment, it should be openly debated on the senate floor.”

According to Murphy, the White House, regulators, and several key lawmakers have all expressed regret for the rider’s inclusion. Officials have responded to criticism with a variety of excuses, but very few have stepped forward to take credit for 735. In fact, most legislators have sought to distance themselves from it.

When blame turned to Sen. Barbara Mikulski (D-Md.), Chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee, she issued a public apology for Section 735. Mikulski explained that although she didn’t support it, her “first responsibility was to prevent a government shutdown,” which meant compromising her own priorities “to get a bill through the Senate that the House would pass.”

What It Does

In one long, legalese-filled sentence, Section 735 basically compels the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to allow genetically engineered crops to grow even if the environmental impact of a particular plant is disputed in court. Although the USDA already had the legal discretion to make this call, Section 735 effectively streamlines the regulatory process to prevent further holdups in the seed market.

Supporters say the overblown uproar over 735 is a reaction born of ignorance, and Monsanto offered to separate “fact from fury” in a company statement evaluating the controversy.

According to the biotechnology and chemical giant, the paranoid portrayal of big business sneaking in a secret provision is “worthy of a B grade movie script.”

“Virtually none of the people protesting actually read the provision itself,” the company’s April 2 blog states. “Those who did, found a surprise: It contains no reference to Monsanto, protection of Monsanto, or benefit to Monsanto. It does seek to protect farmers, and we supported the provision.”

Monsanto says that accusations of backroom deals are not only nonsense, but unnecessary as the measure already enjoyed broad bipartisan support. Commentators have tried to further assuage critics with a reminder that the appropriations bill only lasts six months.

Although 735 does not name the company, Monsanto clearly benefits from the law. Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.) eventually claimed responsibility for adding the provision, and according to an interview with Politico, he crafted the rider in a joint effort with Monsanto and input from the late Senate Appropriations chairman and biotech proponent Daniel Inouye (D-Hawaii).

Blunt, a ranking member of the Senate Agriculture Appropriations Committee, hails from the same state as St. Louis-based Monsanto. He also receives more money from Monsanto than anyone else in Washington. The Center for Responsive Politics reported that Blunt’s campaign committee received over $64,000 between 2008 and 2011.

A Law Takes Shape

According to supporters, 735 is necessary to protect biotech crops from the regulatory holdup of activist lawsuits.

“What it says is if you plant a crop that is legal to plant when you plant it, you get to harvest it,” Blunt told Politico.

The law got its first opportunity for action last week in Oregon’s Jackson County, where organic and conventional growers are looking to ban genetically modified seed through a voter initiative approved for next year.

The ban would protect all-natural crops in the county’s Rogue Valley from contamination with GMO pollen. But some Oregon legislators don’t want the public to be able to make that decision.

State senators on Oregon’s Rural Communities and Economic Development committee used 735 to justify a bill that would mandate a statewide standard on seed planting before the public vote can take effect.

Oregon’s Seed Preemption Bill (SB 633) would ensure a uniform planting policy throughout the state, preventing Jackson County voters from issuing any GMO ban specific to their area. The bill passed the Senate committee 3–2 and supporters now seek a similarly favorably committee in the house.

Proponents of SB 633 say the measure is merely practical, not only because counties lack the resources necessary to enforce a ban, but also because it burdens Oregon farmers with yet another regulatory measure.

Organic and conventional farmers argue that SB 633 targets their business protection.

“Monsanto calls it the Farmer Assurance Provision because they know that language matters. You can get broad bipartisan agreement on something that sounds very innocuous,” said Murphy. “[Farmers] oppose these crops because they could contaminate their fields with the patented GMO pollen. That harms their economic livelihood.”

Last year Monsanto waged a costly campaign to defeat a voter referendum requiring labels on products containing GMO crops in California by painting the law as a liability to consumers. Although that strategy was successful, it was also expensive and difficult. According to Murphy the company wants legislative protections against such voter referendums.

“Monsanto doesn’t want to go to the popular vote. They did it in California but it cost them $46.5 million. It’s an expensive process,” Murphy said. “They want to short circuit the democratic process by doing the easiest thing on earth—by buying the state legislators and elected officials to make sure they do what they want them to do to protect their profits.”