In the heart of Hong Kong’s bustling metropolis, there existed a silent observer whose lens captured the essence of a city in flux. Chan Kiu (1927-2024), a photojournalist luminary, passed away recently, leaving behind a legacy etched in silver halide and pixels.

Photographing 1967 Riots

I began producing the documentary “Vanished Archives” in the autumn of 2012, interviewing those who experienced the 1967 riots. After listening to the testimonies, I checked with the Hong Kong Government Records Service and the Public Records Office. I was shocked to find that despite entering over a hundred keywords, the Public Records Office stored only 21 seconds of footage of the leftist riots, which were spread across nine DVDs. The content is all about demonstrators chanting slogans in Central in May 1967. Footage diligently captured day and night by the Information Services Department under the leadership of then-director Peter Moss had all disappeared.Witnessing Heart-Wrenching Separation During Great Exodus

In the summer of 1987, I interned at the South China Morning Post (SCMP) and got to know Mr. Chan, the then-chief photographer. Having joined the industry in 1956 and the SCMP three years later, Mr. Chan was already quite experienced at the time, orchestrating manpower steadily every day. He was kind and friendly to us young girls and always ready to answer our questions. During the Great Exodus in 1962, when thousands of mainland refugees poured in, Mr. Chan captured an image of a couple bidding tearful farewells.

In the photo, Mr. Yip, who was working in Hong Kong, is separated from his wife and two children who came to reunite, but his wife is immediately detained upon arrival. This image of parting depicts the era and was later turned into a poster displayed outside the entrance of the Hong Kong Museum of History.

Hong Kong has gone through four Great Exodus, also known as “the illegal immigration wave,” since the establishment of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Among them, the three-year Great Famine in 1962 was the most severe, with over two million people flooding in from Guangdong Province. The CCP referred to the Great Famine as the “Three Years of Difficulty” or “Three Years of Natural Disasters,” absolving its responsibility for the tens of millions of deaths due to starvation. In order to survive, people became “river-crossing soldiers” with a spirit of desperate determination.

Coming from humble origins, Mr. Chan had great sympathy for refugees. After submitting enough news photos to fill the pages, he threw away the films of refugees hiding in the woods, not handing them over to the newspaper.

Putting Life at Risk

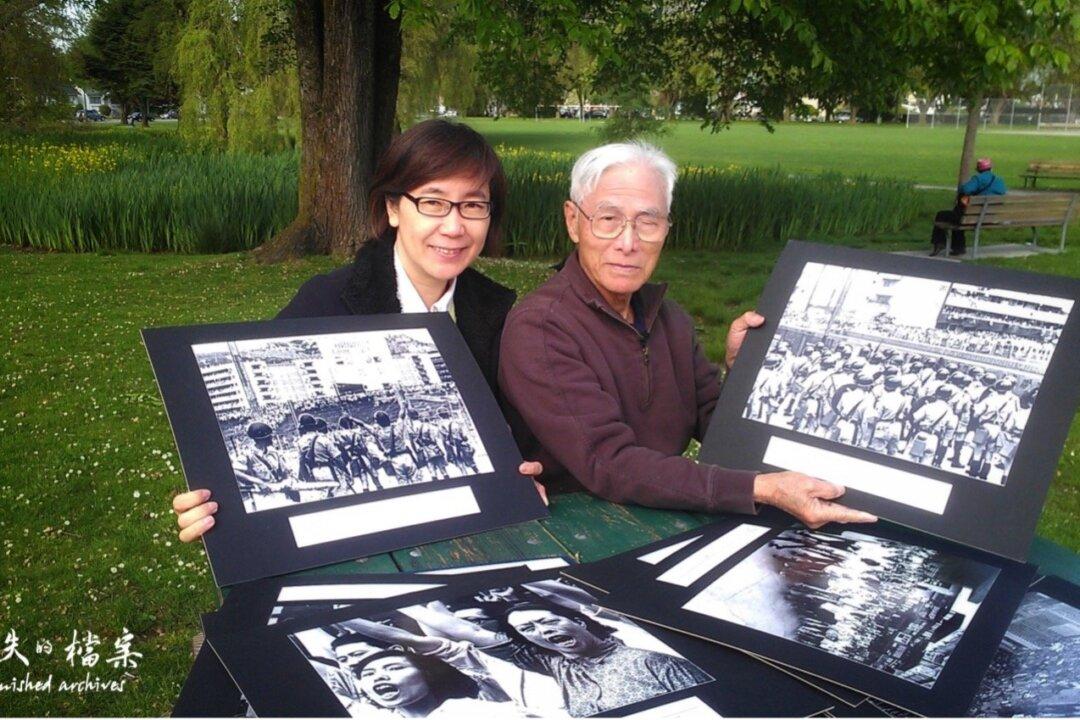

In May 2013, I flew from Hong Kong to Vancouver to interview Mr. Chan. Before departure, I wondered if, at the age of 86, Mr. Chan’s mind was still clear. Could he still remember the details of the 1967 riots? I was overjoyed to find that Mr. Chan could recall everything from the interview and shooting experience to his memories of growing up.Mr. Chan covered the entire process of the leftist riots. He described the frontlines as minefields, with people often inciting in the crowds, “The reporters are beaten!” The riots lasted for eight months, evolving from strikes, demonstrations, and ceasing trade to locally manufactured pineapple bombs (real and fake bombs) all over the streets, threatening the lives of citizens and targeting journalists.

“We would shoot opportunistically, taking a couple of shots and then leave immediately. We couldn’t linger unguarded; it was too dangerous at that time,” he said.

The Left News reporters, who used to be on good terms with Mr. Chan, became strangers to him in those days. Working at the SCMP, Mr. Chan was seen as the mouthpiece of the Hong Kong British government. Chinese people in the media outlet were called “yellow-skinned dogs,” while his foreign colleagues were called “white-skinned pigs,” increasing the danger factor during their joint coverage.

Once, Mr. Chan and his foreign colleagues were stopped on Nathan Road while on assignment. Leftists immediately called for violence upon seeing foreigners. Mr. Chan argued that his colleague was Chinese and demanded passage. In the melee, there appeared a small gap in the road, and the driver hastily accelerated to break free from the encirclement, saving them from harm.

“This photo was taken in Tung Tau Estate. The angle behind the police wasn’t that good. The two of us, Mr. Chan Fai of Sing Tao Daily and I, walked a long way away from the police to take good pictures. But when we retreated, we were surrounded and beaten up. They grabbed our film and watches, hitting us with punches one by one. I almost wanted to cry for help. Fortunately, a young man in white, probably a staff member, came out of the bank and saved me,” he recalled.

Pointing to the location where he stood in the photo, Mr. Chan still spoke with lingering fear. Having lost the film he had shot earlier, he returned to behind the police with pain, got a new film from his colleague, and retook the photo.

“The police dared not to provoke them at the time. They pointed and scolded ... The police were already very restrained. Later, when the situation escalated, the police displayed warning signs: “If you come over here again, I will release tear gas.’ As a result, ‘bang, bang, bang,’ many tear gas canisters were fired. I photographed from behind as those people fled.”

The Committee of Hong Kong–Kowloon Chinese Compatriots of All Circles for the Struggle Against Persecution by the British Authorities in Hong Kong (Struggle Committee for short) was established on May 16, with Yeung Kwong, the then chairman of the Hong Kong and Kowloon Federation of Trade Unions, serving as director and Fei Yi-ming, chairman of Ta Kung Pao, serving as deputy chairman. The Struggle Committee and the Hong Kong and Macao Work Committee called for various fronts to take turns protesting outside Government House. From May 18 to May 21, over a thousand people gathered outside Government House every day, singing revolutionary songs and forcing the adjutants on guard to listen to them reciting Mao Zedong Quotes.

Being assaulted while covering news in Tung Tau Estate did not dampen Mr. Chan’s determination to record history. On May 21, outside Government House, he and other foreign media reporters once again encountered verbal abuse and attacks.

Describing a photo he took at Government House three days after being injured, he said, “These leftist individuals held Little Red Books (Mao Zedong Quotes) and protested outside Government House with a poster. It was the first time in Hong Kong’s history. The Hong Kong government had already been very tolerant back then. They protested every day. We filmed. TV stations and even overseas TV stations also came to film ... At this time, they began to oppose, and arguments broke out here.”

Jack Cater, then-personal assistant to Governor David Trench, met with Mr. Trench every morning at 8 a.m. to discuss the latest situation. Mr. Cater said that the leftist leaders had promised him peaceful protests and would not cause any more trouble.

“We even allowed them to shake the gates and post some stuff.”

Leftist actions continued to escalate, demanding to meet with Mr. Trench and shouting his name outside Government House. Leftist newspapers used slogans like “Hang David Trench” and “British Imperial Executioner,” greatly increasing the pressure on him. Tormented until the end of June, Mr. Trench returned to the UK for a vacation due to health reasons.

Legacy

Mr. Chan had seven children, and he carried a heavy burden of supporting their education. He loved photojournalism and Hong Kong even more, serving as the chief photo editor of the SCMP until retirement. He believed photojournalists must have strong interests, courage, extraordinary bravery, agility, and a keen sense of photography. Taking news photos requires precise judgment, mental preparation before work, and the ability to capture people’s actions and expressions.Mr. Chan accompanied Hongkongers through turbulent times with exceptional skills and empathy. He received over 30 Hong Kong and international honors. He was awarded the Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II in 1985, becoming the only Chinese photojournalist to receive this honor.

Beloved Mr. Chan passed away on April 6, 2024, at age 96, and was laid to rest at Parkview PH3 #1806 in Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Burnaby. He is survived by his seven children, eight grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. The accompanying illustrations in this article are classic photos of Mr. Chan. While he has left us, his photos were authorized by the SCMP to be used to bid farewell to our mentor.